Updating the CPC for Today’s Sign Language Interpreter

Howard Rosenblum presented Updating the CPC for Today’s Sign Language Interpreter at StreetLeverage – Live 2018 | Cherry Hill. In his presentation, Howard shared his vision for updating the NAD – RID Code of Professional Conduct to meet the current realities facing sign language interpreters and those they serve.

You can find the PPT deck for his presentation here.

[Note from StreetLeverage: What follows is a translation of Howard’s StreetLeverage – Live 2018 presentation. We would encourage each of you to watch the video and access his original presentation directly.]

Updating the CPC for Today’s Sign Language Interpreter

Hello, everyone! I’m coming up after two amazing presenters this morning. They are going to be tough acts to follow. Thanks for that!

I am Howard Rosenblum. Can you go ahead and show the first slide, please?

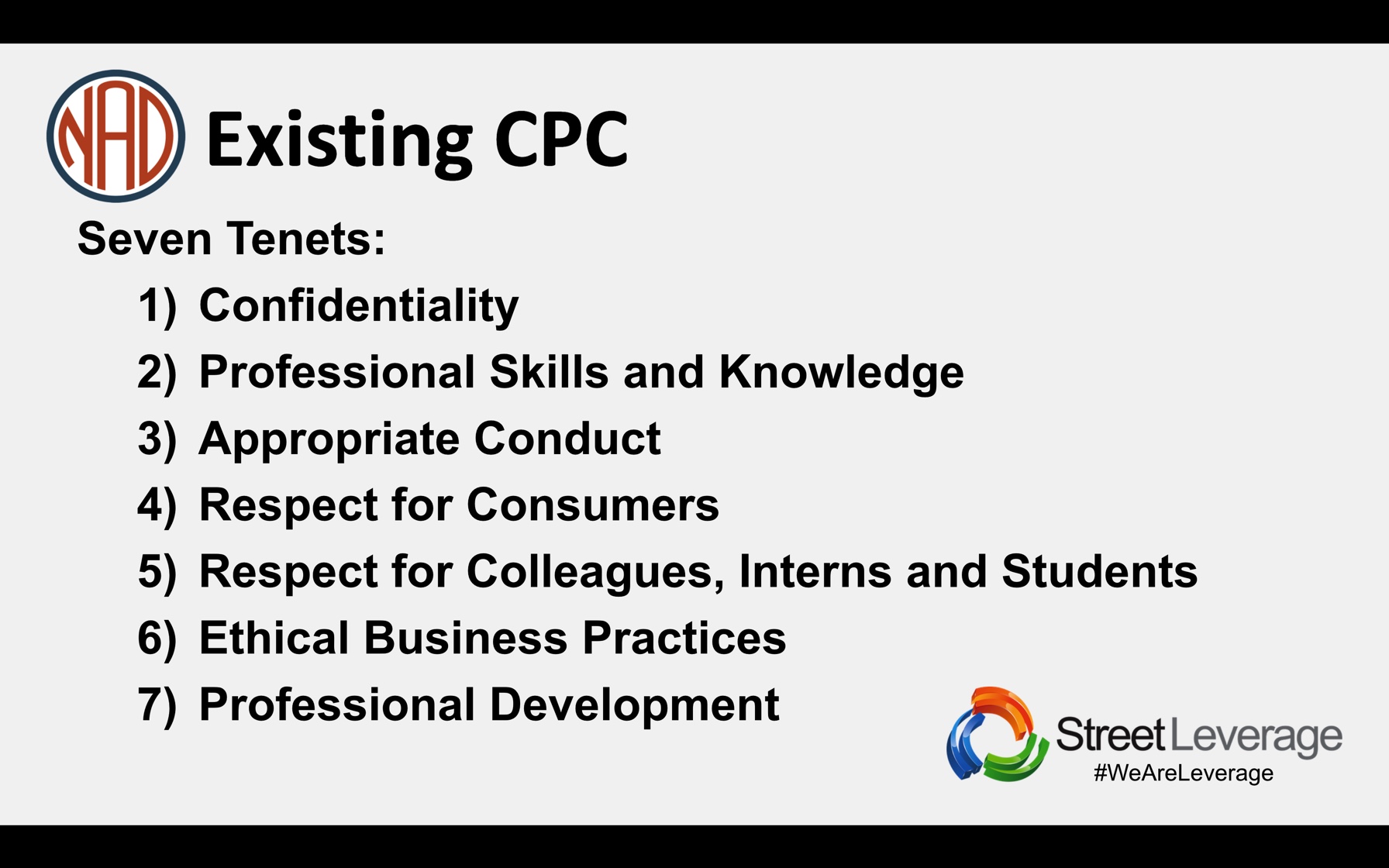

Today’s topic is “Updating the CPC for Today’s World.“ As sign language interpreters, you refer to the Code of Professional Conduct (CPC) for guidance, for reflection on possible courses of action, to respond to your sense that something is amiss. The CPC has been a reliable resource for years. At the same time, the world has changed and continues to evolve. What we are seeing is that the CPC does not address many of the questions and situations that now present themselves. It’s time to revisit the CPC to determine what is present, what is missing, and what needs to be expanded upon. I’d like to start with the seven tenets of the current CPC. I assume you all have those memorized?

These should be familiar to you all. I hope they are. Each tenet is important and they have all been vetted and debated on their merits. One question remains: when are they applicable? Typically, we are focused on the provision of interpreting services – from the time an assignment is accepted to the performance of the actual assignment. What about post-assignment? Is the CPC applicable outside of one’s professional sphere – during daily life? As written, it is not applied in that manner for most circumstances. This is the impetus, for me, in determining the need for an upgrade. Take social media as an example. Hopefully, Interpreters are not engaged with social media while on an interpreting assignment. Outside of their interpreting assignments, however, interpreters are able to engage with social media in a variety of ways. Do interpreters consult the CPC when they consider posting on social media or do they discount it because their social media activity is not related to service provision? We need to look at that issue.

Gaps in the CPC: Public Advocacy

In the past, information was most easily disseminated through publications such as traditional newspapers. If people wanted to share information, they submitted it to RID for publication in The Views, or they sent it to NAD, or to a regular newspaper as an op-ed piece. In today’s world, individuals have myriad avenues to share messages, from vlogs to blogs, online news, and other means. It’s a simple thing to share information on a large scale. When we are talking about public advocacy and the ability to express one’s thoughts on topics such as Deaf rights, the violation of those rights, or calls to defend those rights, we have to ask ourselves, what is an interpreter‘s role? Where is the line between the interpreter’s role and an advocate’s role? Also, many publications have spaces for marginalized voices to be expressed, for example, Queer spaces, Black spaces, Latinx spaces. Where do we hold Deaf space? Where can Deaf people share their lived experiences without other people co-opting that space? Should that be addressed in the CPC? Do we need to define when and where it is appropriate for interpreters to advocate for Deaf people? There are situations where interpreters are needed for advocacy purposes, when we need to call “all hands on deck,” so to speak. However, when it comes to the public dissemination of information, we need to look at how that should be appropriately handled.

I’m not here today to answer these questions, merely to bring them to your attention. I’m here to ask questions: how should we approach revising the CPC? What should we include? What will it look like when we are done? What are the issues inherent in updating the CPC? Those are discussions that need to be had as we move forward rather than maintaining the status quo with the current CPC.

Gaps in the CPC: Publicity and Self-promotion

I recognize that interpreters need to seek work and showcase their skills in order to do that. That is certainly understandable. At the same time, problems arise because the Deaf community is also seeking employment opportunities and doing self-promotion by expressing their ideas, experiences, and skills. When interpreters co-opt that space, trust is lost and the divide continues to widen between the Deaf and interpreting communities. As the gap widens, jealousies begin to develop, communication breaks down, and the divisions increase. Rather than a divide, we need to build bridges between the two communities in order to come together. We must work together but without trust, that is an impossible task. As we see online, anyone can post their opinions. Should we address that in the CPC? It is not currently mentioned. These issues didn’t exist when the CPC was developed. In those days, one person’s experience remained within a small circle. Now, anyone can post information that has the potential to go viral. What would social media rules look like in the CPC? What kind of conversations do we need to have to address these issues? Should there be limits on what can be posted in an ASL vlog, for example? Should an interpreter discuss the Deaf experience in a vlog or should they be limited to talking about their experience as an interpreter only? What are the boundaries? That’s a conversation we need to have.

Gaps in the CPC: Employment Competition with Deaf Individuals

Often, in workplace situations, a Deaf person may apply for a position. What if an interpreter applies for the same position? Is that permissible? How does that impact employment for the Deaf person? If we look at the employment rates for Deaf people, for example, 65% – approximately – I don’t have hard data, but based on research and estimates, approximately 65% of Deaf people are either unemployed or under-employed. That’s a problem. We need to be seeking additional employment opportunities for Deaf individuals. If interpreters seize those opportunities, the result is increased resentment within the Deaf community. And again, we have a reduction in trust. We can’t afford to lose trust. Instead, we need to build it. Deaf people need to be able to utilize sign language interpreters in their employment and other settings. But how can we hire interpreters if we don’t trust them? This is been a growing problem that needs to be addressed through the CPC in order to ensure that we understand the boundaries of appropriate behavior.

Let me give you an example of employment competition. The federal government is the single largest employer of Deaf people in the United States. Often, a job site will have multiple Deaf employees with a supervisor who is not able to communicate directly with their employees. For a time, they may hire interpreters for communication. At some point, they may determine it is better to hire an interpreter as the supervisor of the Deaf employee cohort. This happens quite often. An interpreter is hired at a higher level than the Deaf employees. They no longer act in the role of an interpreter; they become the “boss.” Their superior conveys information to the Deaf employees via this intermediary. This often creates resentment among the Deaf employees as those supervisory positions are usually higher-level government service jobs that typically pay higher salaries and have more status. Many Deaf individuals are looking for opportunities to break the glass ceiling and move up in their career path. Instead, these interpreters have circumvented the system. Should that be permissible according to the CPC? Is that considered oppression or should interpreters be able to avail themselves of those kinds of job opportunities? We need to look at the CPC and develop guidelines for situations such as this, defining what is appropriate and what is inappropriate. I am not the arbiter of these decisions; I’m here to provide the framework for these questions.

Here’s another example. Take a look at work in the performing arts. We have many skilled actors who are Deaf and interested in pursuing careers in the performance arts. Very often, hearing performers are hired into deaf roles. Usually, people who already know some ASL are tapped to play those roles. Often, those folks are sign language interpreters who may have some acting experience. Is that permissible? The CPC currently does not address this issue.

Gaps in the CPC: Adverse Expert Witness Testimony

Adverse expert witness testimony. What does that mean? (Howard knocks his glasses off and catches them.) I got them. That was not part of the entertainment. It was an accident.

In court, sign language interpreters will often be called as witnesses to share their expertise in various situations. That’s fine. Consider a case where a Deaf person is bringing a lawsuit against an entity for discrimination. Can you imagine an interpreter testifying for the defense? Protecting the entity being sued for discrimination? Protecting the hospital, company, or business that discriminated against a Deaf person? Is that hard for you to imagine? I can tell you that it has already happened. Many of your faces convey surprise. “How dare they?“ The CPC does not address this issue. In my opinion, it should, but again I’m not the arbiter of these decisions. I am a lawyer and in all transparency, I am biased.

Occasionally, I’ve seen interpreters testify without realizing that their testimony would cause harm. Some interpreters are fully aware of the consequences of their actions, when that happens, it is a different situation entirely. There are times, however, when an interpreter may not realize how their testimony will be used because lawyers, like myself, may ask an interpreter to talk about their typical interpreting practice. Many interpreters, naively, would agree to testify, thinking they would not cause harm answering a simple question. However, lawyers can utilize their testimony in various ways. For example, a Deaf person would like to become a medical doctor. They want to attend medical school, which is great. While it is 2018, there are still colleges and universities that believe that Deaf people cannot become doctors. They will not accept them into their educational programs. Even though we currently have more than 100 Deaf doctors in the United States, these programs still reject candidates who are Deaf. They tell them that Deaf people cannot become physicians. Obviously, this is untrue as we already have more than 100 medical doctors who are Deaf in the United States. Regardless, the struggle continues. These types of cases often go to court. In those situations, the lawyers for these entities may seek out interpreter educators. They do not explain the purpose of their questions or how the testimony will be framed. They call the educator as an expert witness and ask questions about the interpreting task. Ultimately, they may ask questions like, “Does interpreting have a lag time?” The educator/interpreter witness will affirm that there is a lag time without realizing that the point of the question is to outline the fact that a delay or “lag time“ can be a matter of life or death. Their point is to show that if a doctor is Deaf and there’s a slight delay while waiting for an interpretation, they could be placing their patient in jeopardy. In some cases, that delay might truly be a matter of life or death. So, these lawyers have a strategy when they request expert witnesses. My point is that interpreters misunderstand the strategy; it is imperative that they understand why and what they are testifying about. They must understand which party they are testifying for prior to accepting an assignment as an expert witness. That’s one example of providing adverse witness testimony.

Gaps in the CPC: Adverse Consultations

Many interpreters across the country do various types of work. Obviously, they have to earn a living and I completely understand that. Problems arise when various interpreters or agencies create exclusive contracts for services. There’s nothing wrong with providing services assuming the person is skilled and able to do the work they are contracted to do. But what happens in a situation where the Deaf consumer doesn’t understand the interpreter? What happens when the interpreter is not a good match for that particular consumer? In a situation where an exclusive contract exists, the entity is prevented from hiring other interpreters which creates a barrier for the Deaf person at that hospital or doctor’s office, etc. Where does that leave them? The CPC does not address this issue. The CPC focuses on the assignment itself and says very little about business practices outside of the assignment. The CPC does address some business practices in the current seven tenets but does not focus on the concept of “exclusivity” or the idea that any business practice that can harm the Deaf community is problematic.

Another example of harmful business practice is related to VRI. Many in the Deaf community carry deep resentment for VRI and see it as a form of pestilence to be eliminated completely. There are some people who appreciate VRI because it can accommodate last-minute appointments more easily, it can meet needs in rural locations where interpreters are few and far between. In those cases, VRI can be better than nothing. On the whole, however, most Deaf people would prefer not to use VRI. Part of the resentment of this technology is due to the fact that when it is used, many physicians and nurses are not able to use the technology in the most basic way, like being unable to turn the device on or off. The devices are often unreliable, the video is often poor quality, and the wi-fi signals are often intermittent, at best. All of which creates a substandard experience. Some interpreters participate in the sale and advertisement of VRI as an all-in-one communication solution. Presenting this technology as a solution for a myriad of communication issues, from resolving interpreter availability challenges to preventing interpreters from missing appointments and combating lateness, without contrasting the Deaf community’s poor opinion of the VRI experience is an issue in itself. Is that considered ethical behavior? Again, the CPC does not cover this issue. Again, we need to define the role of the interpreter in those situations. We’re not simply talking about active interpreting, we’re talking about behaviors and actions taken outside of the interpreting task.

Gaps in the CPC: Working for Agencies and VRI that Ignore Customer Needs

This is similar to the previous topic with some expansion. Agencies commonly provide consultation and sales for their businesses. Those are two different categories. Should they be doing what is in the best interest of the deaf community? Should we define and codify the expectation that businesses serving the Deaf community should do what is in the best interest of the community? Or should we simply focus on the work without regard to the impact it may have? Currently, that is a dividing line. That is the space where trust is being lost. Next slide, please.

Time to Update the CPC

Now, I want to shift the conversation slightly. I want to look at why it’s important for us to focus on adapting the CPC to today’s world. I work for the National Association of the Deaf (NAD), but I did not select or determine the tenets of the current CPC. The CPC is the result of agreements made over time between NAD and the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID). I know many people consider that the NAD and RID are going through a “divorce,” so to speak. I would posit that we are still collaborating and perhaps going through counseling. Throughout that relationship, we’ve come to various agreements. The CPC is still labeled the NAD-RID Code of Professional Conduct. The CPC still bears both organizations’ names, and there’s an agreement that still stands between them. Any changes that are made must go through a committee in order to address new challenges and issues, bring up new ideas, and find possible solutions. The committee is currently selecting members from each organization to come together to revise the CPC. I don’t have any idea how long that will take but obviously, the CPC is not something that can be revised overnight. It’s definitely a process and a number of discussions will take place over time. Hopefully, those of you who come to my afternoon workshop can participate in conversation and discussion about various issues, provide your ideas, your experiences, and stories. I will gather and bring that feedback to the committee for review as we begin to develop a new and revised CPC.

If we don’t revise the CPC…I can tell you that the Deaf community’s trust in the interpreting community is at an all-time low. The time is now to review, revise, and revisit the CPC in order to regain the trust of the Deaf community. So, that’s where you can participate. Clearly, the CPC is not the only thing that can lead to the rebuilding of trust. However, the CPC is a guide. It’s a guide that you have utilized for 50 years and it has served you and the Deaf community well during that time. There are some tenets currently in the documents that are applicable outside of the work, for example, confidentiality. That is certainly a value and a tenet that applies across the board whether a person actively providing services or acting outside of the job. At the same time, the CPC, for the most part, does not apply to activities interpreters do on their own, in their own time, and in their daily living. Activities like writing a blog, creating a vlog, or signing a music video – those types of activities aren’t addressed in the CPC currently. The current document primarily focuses on activities during service provision, during the act of interpreting, or while on the job.

If you look at other professions such as lawyers and doctors, their codes of ethics apply to their entire life. As a lawyer, if I do something unethical – unrelated to representing my client – something outside of work that is unethical, I could lose my license. That same concept should apply. Lawyers and medical doctors also have ethics regulating self-promotion and advertisement. A lawyer cannot say in an ad, “I am the best lawyer in the United States.“ That’s not permissible. Claims such as, “I am the best in this specialty,“ are not permissible. We should learn from those professions and apply those standards that have already been established. We see various articles from different people in the field of sign language interpreting, including StreetLeverage contributors, indicating “Do No Harm.“ That concept is implied in these borrowed ideas from other professions. “Do No Harm“ should not only apply during assignments but during an interpreter’s daily living activities within the community and in the world. Messages put out to the broader community can cause harm whether you’re working or not. It’s important for us to look at the CPC together and determine how we can revise the document for the future.

Thank you.