Sign Language Interpreters: Recognizing Your Place in the Deaf Community

Sarah Hafer presented Sign Language Interpreters: Recognizing Your Place in the Deaf Community at StreetLeverage – Live 2017 | St. Paul. In her presentation, Sarah provides native insight on the nature of “travelers” in minority cultures to spark reflections on sign language interpreters and their footprint in the Deaf community.

You can find the PPT deck for her presentation here.

[Note from StreetLeverage: What follows is an English translation of Sarah’s StreetLeverage – Live 2017 presentation. We would encourage each of you to watch the video and access Sarah’s original presentation directly.]

Interested in attending StreetLeverage – Live 2018 being held in Philadelphia, PA/Cherry Hill, NJ (metros) April 13-15, 2018?

Sign Language Interpreters: Recognizing Your Place in the Deaf Community

Good morning. I’m delighted to be here today, and I’m honored to share this presentation with you all. Let’s jump right in, shall we?

To begin, you need to know that I come from a family of interpreters. All told, there are eleven interpreters in my extended family, and I, myself, have been a Certified Deaf Interpreter for the past five years. You could say it’s in my blood.

[Note: presentation shifts to a prerecorded video.]

Hello. My name is Swanhilda Lily. I’m Deaf and come from a Deaf family six generations deep. Having grown up in the Deaf World, I’d like to offer some thoughts on the concepts of culture and heritage.

A culture is defined as a community of people sharing a common language and set of values. With specific reference to the Deaf community, the culture is made up of individuals having a so-called “audiological impairment” as perceived by those in the hearing-centric world at large.

In contrast, heritage refers to the intergenerational passing down of a particular culture. In the Deaf World, Deaf individuals with Deaf parents and codas (individuals who can hear with Deaf parents) are the heritage speakers of ASL and owners of Deaf culture.Together, the members of these two groups (culture and heritage) constitute the owners of the culture.

<end of video>

Swanhilda, the woman you just saw, is my dear friend of many years. Her differentiation between culture and heritage makes for a great starting point for our talk today.

My own journey in coming to better understand culture began when I was just twenty years old, full of wanderlust and eager to see more of the world. Hitchhiking our way from Mexico all the way down to Costa Rica, a friend and I traveled through seven different countries over the course of four months.

Throughout these countries, we really had to work to navigate obstacles of culture and language. I had taken two semesters of Spanish back in college at Gallaudet but had failed miserably both times (the professor tried to teach Spanish grammar through Signing Exact English, but that whole fiasco is a story for another time). We made our way using Spanish-English dictionaries, gesturing, and figuring things out as best we could. Visiting these countries as travelers and outsiders, I began to get a sense of where our boundaries lay.

You see, in these Central American countries, there was no abundance of outsiders from the U.S. or other countries pouring into these villages or tribes and integrating themselves into these communities. Visitors like us were few and far between and had little impact on the everyday goings-on of the places we visited. Now, as a fourth-generation Deaf person from the U.S., these experiences got me thinking about the cultural context of my own everyday life where there is an abundance of outsiders, and they do have a significant impact on the Deaf World.

Before I go any further, let me be clear that the last thing I want to come of my talk is for you to feel put out or inclined to simply disengage from the community that you’re already so invested in. I am fully aware that you, especially having come to a conference like this, have only the best of intentions for Deaf people. My goal, rather, is to help you become more aware of the impact that a majority presence of outsiders in a minority culture has on the culture itself. Hopefully, this will be an opportunity for insight and a raised consciousness for all of us.

So with that said, let’s continue to the next slide. (5:28)

What Does it Mean to Be a Guest?

After my travels, the concept of being a guest in another’s world continued to intrigue me, and I wondered whether that idea held similar significance in other countries around the globe. Running a quick Google search, I found the list you see here on the screen of useful tips to keep in mind when traveling to Bali, in Indonesia. The very first point they make, as you see, is that outsiders must remember that they are but guests in the culture. I was struck by this statement because, thinking back to all my years growing up in the Deaf World, I struggle to think of a time when outsiders were explicitly cautioned to remember their place as guests in our community. I wonder why that is.

Likely, it has something to do with the fact that the American Deaf community exists as a culture within the U.S., a minority community intermixed with the majority. Without ever crossing a border or stamping a passport, a person can meet Deaf people and learn their language and culture. This potentially makes it easier to overlook the fact that, despite the vast amount of time spent in the Deaf World, one is still a traveler and guest.

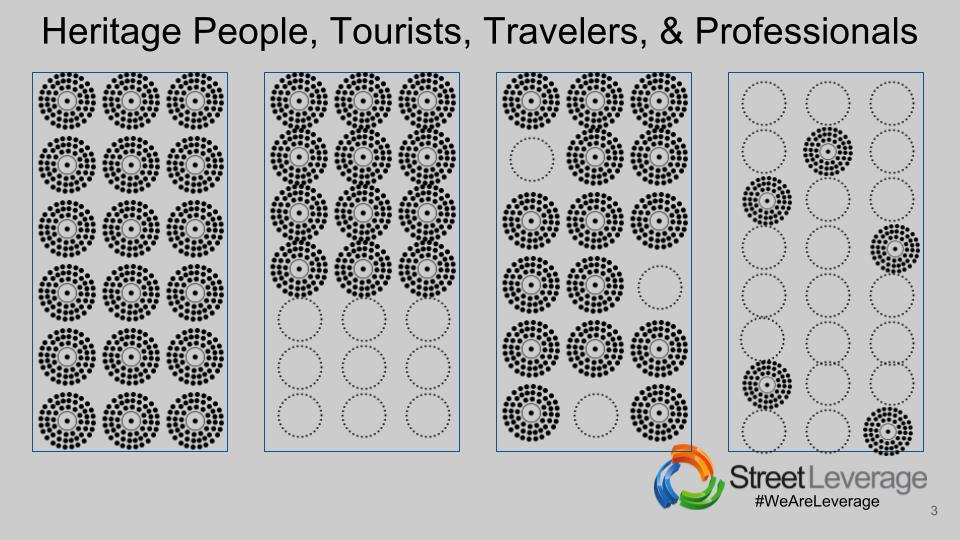

Heritage People, Tourists, Travelers, & Professionals

As you can see, this graphic depicts the four different categories of participants in a given culture. Please excuse the text at the top of the slide; I had difficulty getting the labels where I wanted them.

Heritage People/Cultural Owners

In any case, the first cluster shows Heritage People/Cultural Owners, which represents the core members of the culture, free from outsider presence. This is the community at its best, managing its own affairs. As Swanhilda mentioned, for our discussion today, this group consists of Deaf people and codas.

Tourists

The second cluster portrays the relationship between tourists and cultural owners. Tourists are those who make an appearance, maybe snap a selfie, and call it good. As an example, one can look to ASL students who are required by their professor to attend a Deaf event. Many show up, stay for as little time as possible, and then call it a night without having really interacted with anyone.

Travelers

Travelers are the folks who actually make a time investment into the community by going off the beaten path and getting to know the locals for personal rather than professional reasons. These are the folks who will run into a Deaf person ten years down the road, maybe in the grocery store, and whip out a “NAME YOU?” and a “NICE MEET YOU.”

Professionals

Finally, we have the professionals. Think Deaf educators, ASL teachers, interpreter educators, interpreters, agencies, and the like. By their very nature, they are afforded a place at the table and carry some level of influence in the community. But as the graphic shows, their numbers naturally overwhelm the population of cultural owners.

In fact, were we to imagine a scenario where outsider professionals dominated a cultural group in any other country, we would likely react with discomfort to the consolidation of power in non-members of the culture. Oddly enough, however, we accept this as a pragmatic reality—as a standard operating procedure—for the American Deaf community.

Adopting a Traveler’s Mindset

In order to reassess our outlook on the relationship between professionals and cultural owners in the Deaf community here in the U.S., professionals themselves must adopt a Traveler’s mindset. Remember that travelers neither overrun nor dominate the culture, remaining at the periphery lest they inadvertently dilute the culture. This means walking with cultural owners and serving from behind rather than leading from the front. The willingness of these outsiders to be of service and support wherever possible is greatly valued yet should never come at the price of the core cultural collective central to the Deaf World.

Looking back to our diagram, as we said before, professionals inherently hold a certain level of power and sway in the community. Where a Traveler’s mindset comes into play, then, is in wielding that influence to bring cultural owners into positions of power, so they can call the shots themselves. It also involves deference being given to the will of cultural owners rather than to guests, such as in the case of how interpreters are selected for an assignment. What I find particularly irksome is the manner in which decisions surrounding the hiring of a Certified Deaf Interpreter (CDI) are made. Typically, the hearing interpreter originally assigned to the job is given the final say, rather than consulting either the Deaf consumer or CDIs in the field. This simply is not right. Now, these actions aren’t motivated by any ill intent; there’s simply a lack of consciousness as to what these actions mean. And then, of course, we can look to interpreter referral agencies across the nation, finding that the vast majority are owned and operated by guests who view interpreting as nothing more than “good business.”

One need only refer to the 2015 RID national conference in New Orleans to see how outsider professionals can snub the will of cultural owners. You can only imagine my response when a well-known academic in the interpreting field who happens to be skilled in American Sign Language opted to make her remarks from the platform in spoken English. I was dumbfounded by her decision and the lack of respect it displayed, yet it is but one of myriad examples that go beyond just RID and are indicative of a larger system run by non-owners of the culture. This mindset of entitlement to make decisions impacting the lives of Deaf people is so prevalent that Deaf interpreters eventually resorted to establishing the DIC, a separate conference focusing on the work of Deaf interpreters. Were RID truly listening to the very people they purport to serve, I doubt this would have ever been necessary.

Therefore, in order for us to address the underlying issues at play, it is imperative that outsiders participating in the community adopt a Traveler’s mindset, one of being a guest in another’s world. They must embrace an approach whereby professionals who financially benefit from the work they do hand the reins over to cultural owners.

Systemic Oppression: A Personal Story

At this point, I’d like to bring things to a more personal level and talk about my firsthand experience with systemic oppression and resistance guided by the wise words of my father.

Growing up, my school had a policy requiring everyone to use their voices while signing. Only one of my other classmates was also from a Deaf family (he is the sixth of the nine Wilding family kids, very well known in the Deaf World), and together we were the headstrong resistance to this policy. Being from signing families, we felt empowered to push back and stand up for our communicative rights. This just wasn’t the case with the rest of my class. So the two of us made a pact to completely stop speaking while signing, and the next day when I made good on our promise, our teacher gave me an F for the day… and she did so every day after that. By the seventh day, she was so angry that her strategy wasn’t making a dent in my resolve that she kicked me out of class.

Now, any time I need to get something done, I want to go straight to the top where change can actually happen. I don’t have time to jump through hoops. That particular day, I decided to go right to the superintendent’s office.

I explained the situation to him and the reason I was refusing to use my voice in class, to which he responded that school policy required it. So naturally, I asked to see the policy in the handbook. Completely caught off guard, he flipped back and forth through the pages, desperately trying to find the verbiage that would put an end to my protest. A bit dishonestly, he finally pointed to a policy that he hoped would be too complex for me to comprehend. But as it turns out, I understood the policy perfectly well, and in no way did it require any student to use their voice in the classroom. What it called for was essentially a “by any means necessary” policy to ensure that communication was successful between students and teachers. Rather unappreciative of my helpful correction to his misinterpretation, he sputtered, spit out his chew, and ordered me out of his office.

I can tell you now that in that moment, for the first time, I understood oppression at a visceral level. The fact of the matter is that I’d been dealing with oppression my entire school career in the form of teachers who couldn’t even speak my language. But it had always been easy to see each teacher and each confrontation individually, passing them off as isolated incidents of incompetence and ignorance. Now that I was actually standing up for myself, the demands that I acquiesce to their oppressive mandates affected me differently, and I was finally able to see it for what it was. Yet for all my bravado, I was still only a fourteen-year-old child. Being thrown out of the superintendent’s office pulled the rug right out from under me, and I cried all the way back to class.

Long story short, I ended up in front of the principal later that day, where I was told that my father had been called and was on his way to the school for a meeting. I immediately became hopeful because my father’s own school experience years before had been nothing short of horrific, which I hoped would work in my favor.

The principal himself was not a great signer either, so when my dad arrived, I jumped in to give him a run-down of the situation. Immediately, he set his crosshairs on the principal and unloaded on him. Years of frustration about his own oppression and limitation from the school came flooding out in a torrent against which the principal had no defense. To this day I still replay that scene in my mind.

Completely taken aback, the principal relented—I wouldn’t have to use my voice any longer. However, he insisted that I continue mouthing English words while I signed. Certain my father would never agree to something so absurd, I waited for round two of the shellacking. So you can only imagine my utter shock when he accepted this new stipulation. “But, Dad!” I began to protest, though he immediately interrupted and assured me that he’d explain when we got home. My father was a wise man, and what he eventually told me that day has stuck with me ever since. He told me that change doesn’t happen overnight. Societal change is akin to walking a tightrope. With each step forward, the rope swings back and forth and the acrobat must wait until a new balance is restored. Only then will another step bring them closer to the other side instead of to the ground below.

One Step Forward, Two Steps Back?

For the first time in my life, I am beginning to doubt the wisdom of his words. The funny thing about taking it slow in terms of progress is that every time we take a step forward, someone moves the finish line one step farther away. So are we really even making any progress? I’m not convinced we’re getting anywhere because we’re a fractured community, spinning off in endless directions. The result is that we are lost and broken souls, not in control of our own destiny. I know you all mean well and want to be supportive, but how do we respond to the fact that you simply outnumber us?

Take RID’s membership, for example. Currently, there are something like 16,000 members. Out of that, approximately 300 are CDIs, and two or three thousand or so are codas. Does that seem right to those of you in the audience? That means there are roughly 13,000 guests in our field. We don’t see this degree of disparity with other languages and cultures around the world. So how do we maintain the integrity of Deaf culture? The only adequate solution is for these guests to adopt a Traveler’s mindset and begin to support from behind, leaving the most influential posts to cultural owners.

Accept No Imitations

This has been a somewhat heavy talk today, so before I close, let me ask—who here loves chocolate? I’m a total chocoholic myself. On the slide, you see fudge on the left and a “chocolate” (I use the term loosely) bar on the right. The fudge is rich, pure, and delicious, while the so-called chocolate bar only has the tiniest of chocolate stripes across the top. (You’d think the company could produce something better, but whatever.) My point is that it hints at the real thing but falls short. So, in closing, I ask you, which would you prefer: the realness, richness, and authenticity of actual Deaf culture or a watered-down imitation?

Thank you for engaging in my talk.