When sign language interpreters avoid addressing issues to minimize conflict, we are exercising hearing privilege by adhering to majority cultural norms. Acting in true allyship requires courage, professional discipline, and transparency.

As sign language interpreters, we constantly make judgment calls on appropriate language choices and cultural behaviors in addition to determining how/where to act in allyship1. In recent years, the concept of social justice2 and community accountability have become central to the discussion about how we practice the work of interpreting.

What is Polite Indifference?

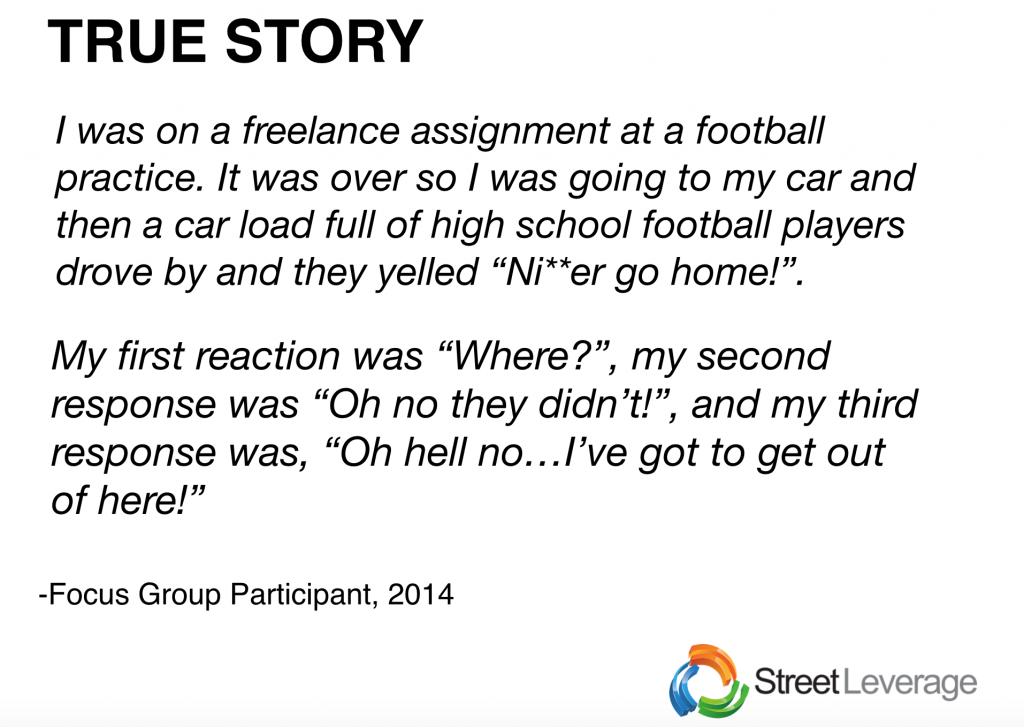

Within the context of sign language interpreting, “polite indifference” refers to the American hearing cultural norm that results from the value of minimizing interpersonal conflict. When the risk of error is minimal, we drop the issue. We ignore the wrong. As people who are a part of the linguistic majority, we hold this privilege. As sign language interpreters, we use this privilege to decide if the situation is worthy of case discussion3 and/or involving the Deaf person in the conversation. These are decisions we, the interpreters, make daily. When a sign language interpreter decides an indiscretion is minor and not worthy of discussion, time or attention any kind, we are exercising our hearing privilege by practicing polite indifference.

Polite Indifference in Action

At one very public assignment, I was teamed with one hearing interpreter and one Certified Deaf Interpreter for a presentation which many Deaf community members attended. My colleagues were watching, listening, and undoubtedly, making note of my work. If I were in their seat, I would be doing the same. As I began to interpret, things were fine, but as time wore on, my team never took the microphone. As my mental process was breaking down, I could hear my own voice speaking English, but it wasn’t pretty. Sure, the concept was there – the main points were touched on (thank you Sandra Gish!4) but the extended time spent processing the source language and producing the target language without a break was clearly wearing on the interpretation.

By the time my team did take the helm, I was already spent and wondering why I had continued for so long, alone. The assignment continued in the same vein, with me taking the bulk of the ASL to English work. At the conclusion of the assignment, I fled to the restroom to gather myself. I needed to figure out how to approach my teams. While I have a good, strong relationship with this team, I was struck helpless. Worse still, we had agreed to meet with four less experienced interpreters so they could observe our debriefing session. I was not in the mental or physical state to engage in the kind of conflict I was feeling with spectators present.

As the debrief began, my hearing team confirmed my suspicions; with our colleagues in the room and the rich content of the presentation, she lost her mojo. I know that feeling well. She said she thought I was doing a fabulous job. My heart sank. Even if that were true, I wanted to scream at her for leaving me alone without switching at the agreed upon time. I wanted to ask her to prepare by knowing the terminology prior to coming to the job. I wanted to tell her I expected more from her. I wanted to tell her she let me down.

When it was my turn to debrief, I couldn’t bring myself to say anything about how I was feeling or what my process was during work. With four pairs of new interpreter eyes focused on us, I wanted our process to look shiny and positive; I wanted to make the best of it. I was embarrassed to have them see us fail at working together. The assignment was rife with rich content and process dynamics. It felt petty and personal to discuss my concerns about being left to do all the work. Plus, I was so tired; I couldn’t accurately judge the caliber of my own work. Instead of speaking up, I decided it was easier to be politely indifferent to what happened. To let it go.

After the debrief, I was left with several questions: Did this session meet the expectations of the new interpreters? Would the interpretation meet the expectations of the presenter? Will this team of interpreters be able to work together again? What have I done??!

In my community of practice, we share concepts of accountability including: calling out oppressive behaviors, recognizing micro-aggressions and audism. We discuss these concepts in the hopes of unpacking and addressing the privileges we have brought to interpreting. But in deciding to be quiet that day, I erased it all with my “polite indifference”.

Using Our Voices for Good

As I work with new sign language interpreters, our debrief allows me to see the impact of staying silent, even if there are perceived advantages. Some mistakes I have made go untouched, undiscovered, but having mentees requires me to look at the mistakes and deconstruct what is happening in my work. The difference between staying silent and this work of deconstruction is staggering. I practice case conferencing which elicits community involvement and takes into consideration the perspectives of Deaf people, my team, and the hearing constituents. I ask new practitioners who are still deeply entrenched in academic concepts to consider the impact of the work on all stakeholders.

Privilege is a fact which is central to our business. As hearing interpreters, our work is predicated on our ability to hear. Because of that privilege, because we are in the majority linguistic culture of the U.S., because we practice interpreting to provide access to information, we must always be mindful of the power privilege carries in our work and use our voices for good. This means having difficult conversations even when we feel that twinge of conflict and desire to be polite. We don’t always have to agree on each facet of the conversation. Acknowledging the temptation to respond with polite indifference will ultimately lead us to better outcomes and better relationships with Deaf people and team members.

Now what? Steps Forward

Addressing polite indifference and unpacking our privilege allows us to be more transparent. We must acknowledge that we have privileges and use them in a socially conscious way. If we do not share our thoughts, feelings, patterns and discomforts, we remain complicit in oppression and polite indifference can easily become a habit in our work. Unpacking is not comfortable. We have to remember that this action comes from a compassionate and ethical practice which is grounded in social justice values. A large majority of sign language interpreters are second language learners of ASL.Sharing our thoughts and feelings about our work is hard. Hearing the feedback of others is not easy.

In the situation described above, my decision to withhold information was an exercise of my privilege. What drove me not to share information was polite indifference. Much later, when I clearly understood my obligations, I talked to my hearing team. We hashed it out. I talked to my colleagues. They assured me the message of the presenter was given. I hope to speak to the observing interpreters individually and talk about the missed opportunity for discussion, and how recognition of polite indifference is a critical component in our work. Someday I will have the chance to talk to the presenter and organizer. The ultimate lesson for me is that polite indifference is the opposite of using my voice for good.

Questions to Consider:

- Recognizing privilege is critical when working with marginalized populations. How can sign language interpreters support each other in recognizing when hearing privilege is guiding decision-making in an interpreting situation?Do you feel prepared to have these difficult conversations with your team? if not, why not?

- How can sign language interpreters address issues of power and privilege proactively in team situations in order to protect the integrity of the work?

- Think about an instance when you chose polite indifference instead of confronting an issue. If you could go back in time and relive that situation, what would you do differently? Why?

Related Posts:

Missing Narratives in Interpreting and Interpreter Education by Erica West Oyedele

Self-Awareness: How Sign Language Interpreters Acknowledge Privilege and Oppression by Stacey Storme

Power Dynamics: Are Sign Language Interpreters Getting it Right? by Darlene Zangara

References:

1 Allyship. (2011, December 10). Retrieved October 26, 2015, from https://theantioppressionnetwork.wordpress.com/allyship/

2 Coyne, D. (2014, May 20). Social Justice: An Obligation for Sign Language Interpreters? Retrieved October 26, 2015, from http://www.streetleverage.com/2014/05/social-justice-an-obligation-for-sign-language-interpreters/

3 Keller, K. (2012, February 28). Case Discussion: Sign Language Interpreters Contain Their Inner. Retrieved October 26, 2015, from http://www.streetleverage.com/2012/02/case-discussion/

4 Tag: Sandra Gish. (n.d.). Retrieved October 26, 2015, from https://theinterpretingreport.wordpress.com/tag/sandra-gish/