Real-life case discussion brings a myriad of benefits to us as sign language interpreters. Kendra Keller highlights how engaging in supervised, structured case discussion can lead to not only enhanced technique but a deeper relationship among us doing the work.

As sign language interpreters, we continue to struggle with the very real human costs, the fallout from the gaps in our professional development and consideration of each other in our work. As we continue to evolve in how we discuss our work with each other, we need to consider a process which will assist us in staying engaged with consumers and all aspects of our work.

Case discussion, in the context of supervision, is an important tool sign language interpreters have available to them for this very purpose. Case discussion is a professional space to hold discussions using our actual experiences, in a shared commitment to uphold ethics, confidentiality and a collective process.

Case Discussion – How it Works

The structured process of case discussion allows for sufficient support without constricting the actual discussion and helps to highlight, tease out and identify the interpreting decisions made in the face of the tasks we are confronted with while on the job.

As a result of this process, case discussions become a mirror of the individual process, reflecting back to the individual the effectiveness and ethicality of their work via the light of many eyes, minds and hearts. This guided self-discovery provides a profound and meaningful learning opportunity.

Redirect Fight or Flight

What is it that keeps us from effectively talking about our work? As mentioned above, as a profession, we continue to struggle with the very real human costs, the fallout from the gaps in our professional development and consideration of each other in our work. Sign language interpreters, like those in other helping professions, show a trend of being hypercritical of our selves…[and therefore, others]…(Feasey, 2002). This hypercritical response grows to a tipping point where we are expelled from a process engaged with team and consumers, into some version of a fight/flight defense reaction. Operating in a state of flight or flight limits our engagement and awareness of others except as the source of potential threat and therefore, options, thought worlds, culture, and communication dynamics. This stance preempts our awareness of choices, or controls – thus hobbling an effective and ethical decision-making process. This occurs when we are interpreting as well as in discussion with colleagues. It could be seen as an inherent ‘system failure.’

Shared Process

When managing the complexity of the task results in a system failure for the working sign language interpreter it can be attributed to two things, if you apply the thinking of Gorovitz and MacIntyre in Atul Gawande’s The Checklist Manifesto: How To Get Things Right:

- Ignorance. The partial or incomplete understanding of the task and its complexities.

- Ineptitude. A failure to apply what we know correctly.

This ignorance may simply be that we may not be aware of what we don’t yet know. Research shows that in some settings we may be unaware of controls or do not feel we can use them if we are aware of them. (Dean and Pollard, 2010). Alternately, our concept of role and interpreter presence may be constricted; we may not be aware of a demand to be able to respond with an effective control option. For example, the interpreter who is trying to be ‘invisible’ fails to consult with the Deaf and hearing consumers before and after an assignment or during breaks, overlooking the consumers’ needs. We may not realize that the decision to spell out the same word repeatedly for which there is an agreed upon sign creates more visual noise and even a foreignalization or word which looks like a new vocabulary item to the deaf person. We are not aware of the fact that we are responding to many demands, that we are making decisions; nor are we aware of the consequences of them.

Ineptitude can be described here as overwhelm at the complexity of a task. A pilot who has 20 years of experience flying a variety of aircraft, and is charged with flying a new aircraft with twice as many tasks to perform results in a crash landing during a test flight. A sign language interpreter who knows how to keep the processing transparent yet in a high stress situation reacts with an “I missed it, what did they say?!” urgency in the middle of a feed from their team. Our thinking and processing may also be occluded by our own self-criticism or fear of failure, resulting in an inability to hold our attention on the work, much less to discuss it with colleagues.

The importance of a shared process is that it provides a framework, the creation of a schema, systematizing our decision making process, which is inclusive of more factors than one person may be able to retain and respond to in a given moment, aids in recall, recognition, recourse and supports the elimination of this (unavoidable) human ignorance and ineptitude.

Presenting a Case for Discussion

The concern about confidentiality may lead to an avoidance of talking about our work. Through effective case presentations, sign language interpreters learn to practice confidentiality, by sorting out the important details and a reason for bringing it into discussion. It might be the more mundane situation which is the greatest gem for discovery. Situations we interpret on ‘automatic pilot’ – perhaps therefore using a less considered decision-making process and habituated responses, are the most fertile ground for searching for clues to consumer reactions that we are mystified by; or responses from teams or others which appear to be mirroring the opposite intentions we are working under. It may serve us equally as well as discussing a profound experience.

Important Aspects of Case Discussion

Commitment: A commitment is to participation in a reflective process, to brooking both the familiar and unpleasant or unwanted aspects of our work for the gain of insight. Each participant has to be committed to creating a process individually and as a group, “by each member to the interrogation of one’s own beliefs and assumptions as well as of others” (Kennedy and Kennedy, 2010).

Facilitation: It is the role of the facilitator to jump in during learning moments; redirect, restate, restructure the interaction or reflect back to the group. It is essential to clarify and establish the role of the facilitator – participants discuss and agree on a dynamic set of ground rules. Remember, the facilitator is responding to maintain the structure of the interaction acknowledging the potential for perceived interruptions and taking the floor as rude and disrespectful, which needs to be clarified (R. Dean, 2010, personal communication).

It is important to work with a facilitator who is trained to lead case discussions in the supervision context. One who possesses the skills and experience required for supervision – cultural sensitivity, knowledge of the myriad approaches to an interpreter’s professional development and of group dynamics.

Ground Rules: Creating the safety needed for a vibrant discussion and protection of confidentiality is supported by setting effective ground rules. Agreed upon rules encourage a ‘scientific’ type curiosity, supported by a critical thinking consciousness and a sharing of perspectives as equals. Some examples of ground rules are:

- Confidentiality: for example, discussions outside of the formal meeting should be brought back to the group, all case notes are collected and shredded/deleted.

- One conversation at a time.

- Recognition of the privilege we have as interpreters: sacred place; serious ethos.

- Agree to disagree: recognition of valid but competing values.

- Avoidance of the need to ‘fix’ or provide solutions – referred to by Parker Palmer as the Righting Reflex.

- Inquiry and clarification to allow seeing the case elements as the interpreter presenting sees them.

Ground rules should focus on supporting the delivery of valuable feedback to the recipient, not on the value or “release” that it provides the person giving the feedback (Lehner, 1975).

Schema and structure: for example, the use of the demand control schema, developed for sign language interpreters out of concern and compassion, focuses case discussions on identifying and decreasing contributing factors that cause undue stress and contribute to ethical dissonance.

Preparation: It is important to make the case available before the group meets so that participants can familiarize themselves with its details. Cases may be both retrospective or prospective, looking back or looking forward in preparation.

Methods: Case discussion groups can use online discussion boards, live video conferencing, and online classroom environments to do their reviews. Of course, let’s not forget that they can be conducted in small groups or 1:1.

Group process: This process supports the development of interpreters’ ability to dialogue with one another in a deliberate problem solving, community-building manner. “Emphasis is placed on the capacity to remain sensitive to context and the beliefs of others” and “…a community of interpretation which we understand as a spontaneous human discourse form…” (Corrington in Kennedy & Kennedy 2010).

Benefits of Case Discussion

The practice of Case discussion and the associated preparation and analysis help sign language interpreters remember or recognize details, realize that we are making myriad decisions on the fly by responding to a complex constellation of demands, and expands our response options. We better understand the sheer complexity the work and deepen our appreciation of the human elements of what we do. Vicarious learning with our peers lessens the ignorance, shedding light on the complexity and developing a systematic approach helps to prevent failures of ineptitude.

In short, case discussion creates a process and setting which helps sign language interpreters contain their inner “What the…!!!?” long enough to engage with the person/task at hand and do the most effective job possible.

What Can You Expect?

Sign language interpreters using case discussion can expect to:

- Reflect on the applicability of one’s own knowledge, skills and attitudes or values (FAO Corporate Document Repository).

- Develop or enhance individual schema or collection of schema for use by sign language interpreters when working.

- Develop a common language for describing one’s process.

- Experience growth in negotiation skills with colleagues and consumers.

- Participation in and development of “double- vision” for monitoring the process simultaneously with the content. This procedural awareness allows for appropriate authorship of decisions and outcomes with direct application to the individual interpreting process.

- Reveal the complexities of the work, as well as the discovery of similar complexities others are dealing with and similar or common decision making strategies.

Let’s Return to the Conversation

Let’s converse with each other in a manner which does not diminish us by limiting our discussions solely to technique (Palmer 1998). The process of case discussion in supervision strengthens our relationship to our communities. Case discussion is ultimately a wellspring of shared experience, building upon the natural processes from within our communities in a manner both considered and reflective (including our Deaf and Coda communities). Case discussion assists sign language interpreters in the development of a common language for describing our process, to gain or hone negotiation skills with colleagues and consumers.

The effective use of Case discussion supports growth in a sign language interpreter’s ethical decision making, learning to trust each other to a greater degree…we begin, and return to, the conversation.

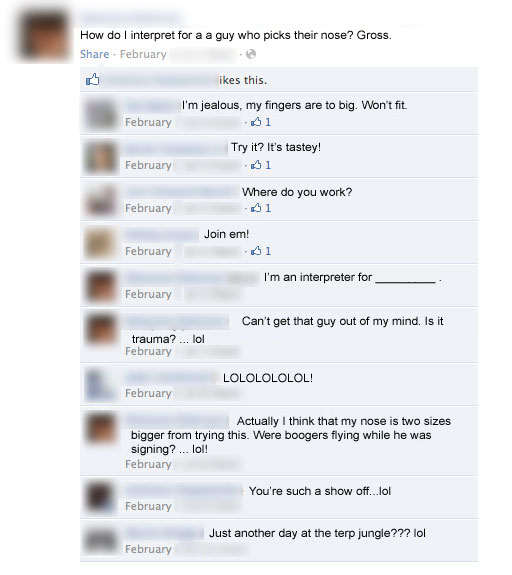

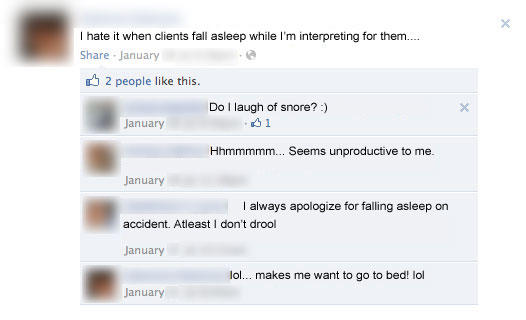

Symptom 4: The Interpreter views digital content as temporary. They fail to understand that digital content, particularly images, will remain forever.

Symptom 4: The Interpreter views digital content as temporary. They fail to understand that digital content, particularly images, will remain forever. When interpreters telegraph opposing political opinions, an emotional disposition, or intimate windows into their personal life, it may lead to reasons for incompatibility with the consumer, and thus the assignment. You may have noticed in the comment section of Brandon Arthur’s post,

When interpreters telegraph opposing political opinions, an emotional disposition, or intimate windows into their personal life, it may lead to reasons for incompatibility with the consumer, and thus the assignment. You may have noticed in the comment section of Brandon Arthur’s post,