Why don’t POC enter the field of sign language interpreting in higher numbers? Why don’t Interpreters of Color stay in the field? Find out more about these questions in our five-part series by a group of CSUN researchers.

Introduction

Throughout the ages, Deaf people have used sign language interpreters, from mid-17th-century religious services to the opening of Gallaudet University in 1864 (Van Cleve & Crouch, 1989) to every domain in society today. While the field of sign language interpreting has a rich and varied history, the racial demographics do not have as much variation. Sign language interpreting in the United States is an occupation dominated primarily by white women, and the legal foundation for sign language interpreting services is based on disability law, which creates a continuing perception and gender-based expectation that such interpreters are service-providers, caretakers, organized volunteers, or non-professional service providers (Merithew & Johnson, 2004, p. 18). Although the gender issue is well documented, an in-depth analysis of the racial demographics in the field has not been adequately addressed.

[Click to view post in ASL]

In Erica West Oyedele’s thesis, African American/Black interpreters report that their white colleagues lack cultural competence. This perspective is echoed by Asian American interpreters, Latinx interpreters, and Deaf minority consumers. Further exacerbating this problem is the notion that Deaf people are labeled as “diverse” simply due to their non-hearing status. Racial identities among members of the Deaf community are rarely acknowledged (Parasnis, 2012). The Black Deaf community has been largely ignored, and their unique experiences have been essentialized to the dominant white group (Foster & Kinuthia, 2003). This portion of the community is being wholly underserved due to a lack of recognition and cultural competence among predominantly white sign language interpreters. The field of sign language interpreting also lacks publications concerning people of color (POC) which further elevates the relevance of our research and the urgency of the issue.

How We Came to this Study

The four authors of this study come from various backgrounds, multiple identities, and different connections to the field, yet all are actively involved in the fields of Deaf Studies, sign language interpreting, and the inherent issues which surround the interpreting field. We each contributed our own areas of interest and focus to this study. Dr. Lissa Stapleton focused on the religious and spiritual connections to the sign language interpreting field. MJ Jones is a graduate student who focused on the lack of support and mentorship for interpreting students of color. Jasmine Ruffin is an interpreting student whose area of focus is on how an individual’s confidence, mentality, metacognitive perception of oneself, and environments influence achievement and character building. Dr. Will Garrow is focused on how -isms intersect and impact communities and how those communities resist the -isms they face on a macro, meso, and micro level.

We came together because of a shared interest in understanding why there was such a lack of interpreters of color at the professional level and in Sign Language Interpreter Education/Training Programs. The goal of this study is to begin uncovering the issues that are creating barriers for POC to become interpreters. We focus on the IEP program at CSUN. We examine how hearing POC are limited in their choices of work and how a lack of Interpreters of Color (IOC) impacts Deaf People of Color, perpetuating audism, racism, and other -isms onto this group of people.

Theoretical Overview

For our research, we decided to use a phenomenological approach when interviewing participants. Our goal was to explore the lived experiences of POC and whether those experiences had an impact on their decision to join or not join the sign language interpreting field. Phenomenological research “seeks to explore, describe and analyze the meaning of individual lived experience: how they perceive it, describe it, feel about it, judge it, remember it, make sense of it and talk about it with others” (as cited in Patton, 2002, p.104). We conducted in-depth one-on-one interviews with individuals who have experienced a “phenomenon” of interest in, but not limited to, American Sign Language exposure, education, and career choices regarding the field of Deaf Studies and sign language interpreting. The importance of analyzing student experiences and life stories was rooted in the assumption that there will be commonalities or shared experiences amongst participants that can be viewed as unique expressions and then compared to identify the patterns or root of the phenomena (Marshall, Rossman, 2011 p. 19-20).

Our analysis of the interviews was driven by Critical Race Theory (CRT) because of the five tenets that guide CRT:

- The intercentricity of racialized oppression: the layers of subordination based on race, gender, class, immigration status, surname, phenotype, accent, sexuality, ability, etc.

- The challenge to white dominant ideology

- The commitment to social justice

- The centrality of experiential knowledge of POC

- The transdisciplinary perspective (Delgado and Stefanic, 2012; Yosso, 2006).

We viewed students as individuals who constitute a complex intersectionality of identities and therefore faced multiple forms of oppression. A holistic view of students created a lens that centralized our analysis of student experiences and educational disparities, by specifically focusing on students of color, which emphasized the importance of race (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Specific to this study, the tenets of CRT provide a framework to analyze the complex weave of macro-, meso-, and micro-aggressions which have created educational disparities and thus impacted the choices that students make when picking a major, their success in a chosen major, and then ultimately which occupations they pursue.

Participant Overview

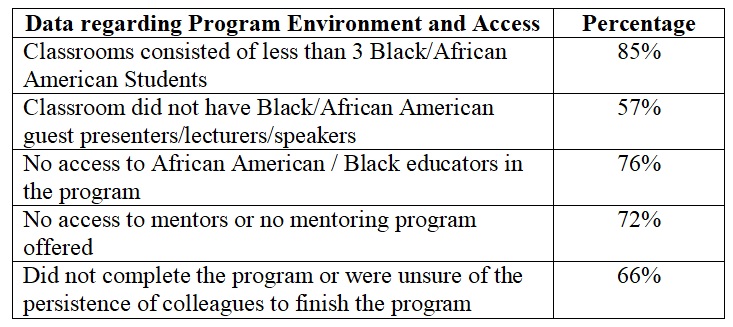

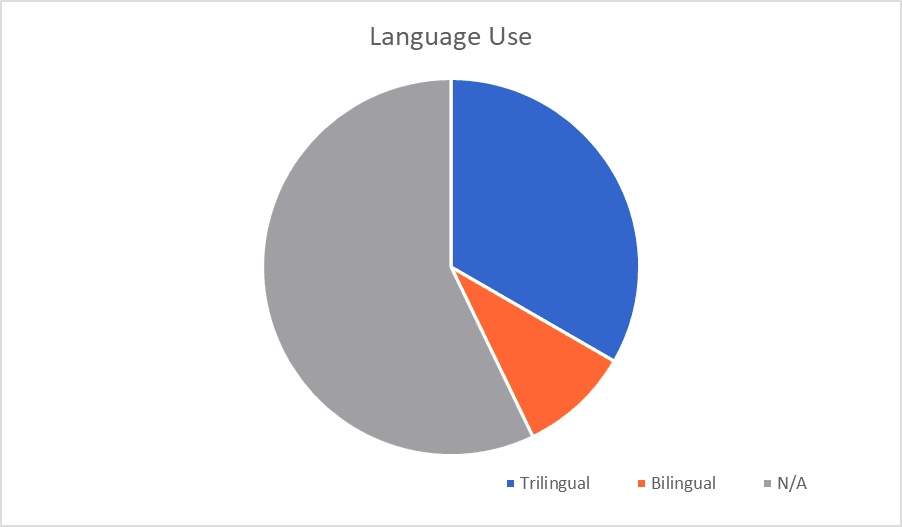

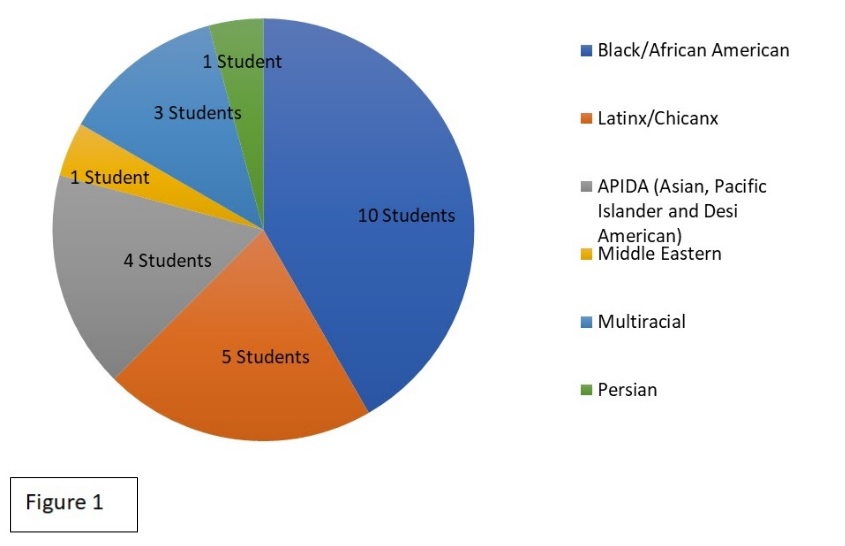

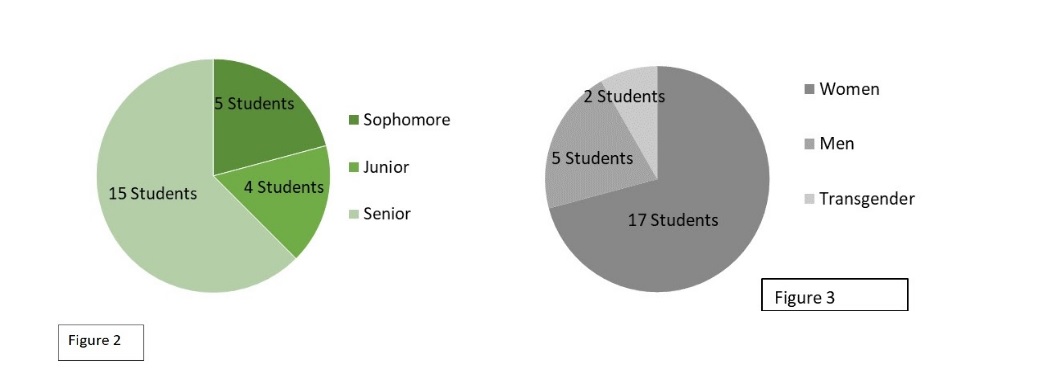

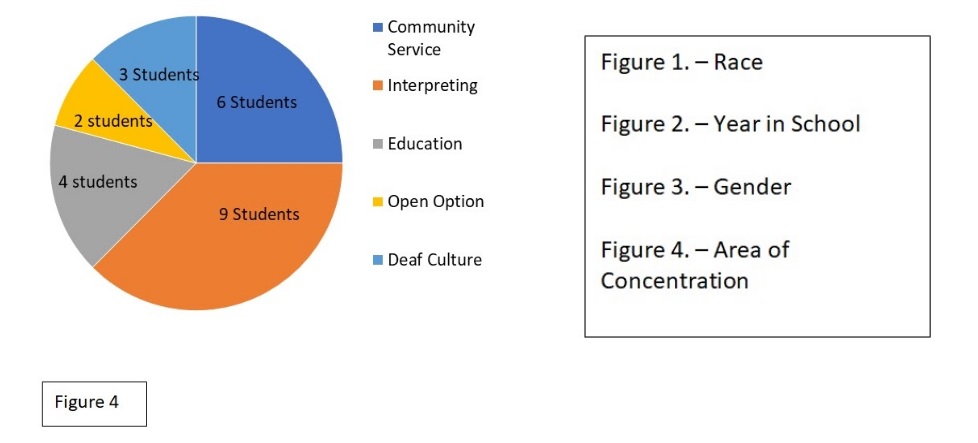

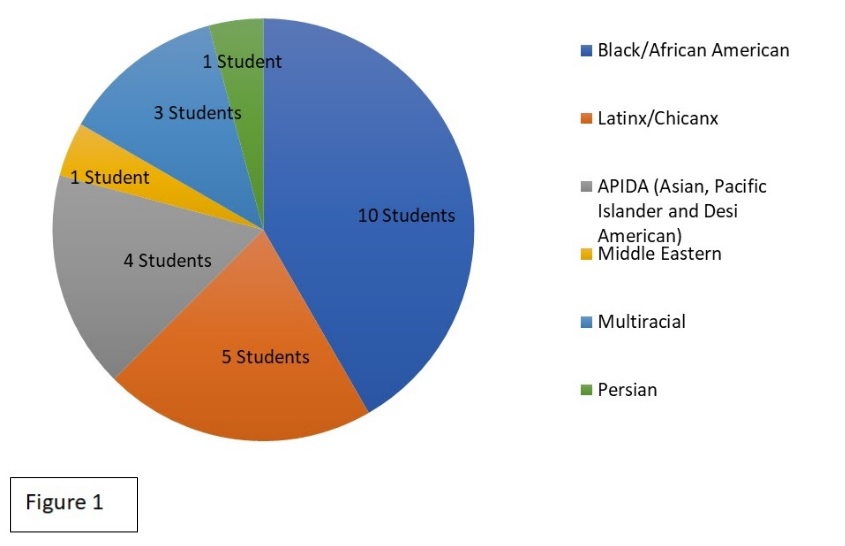

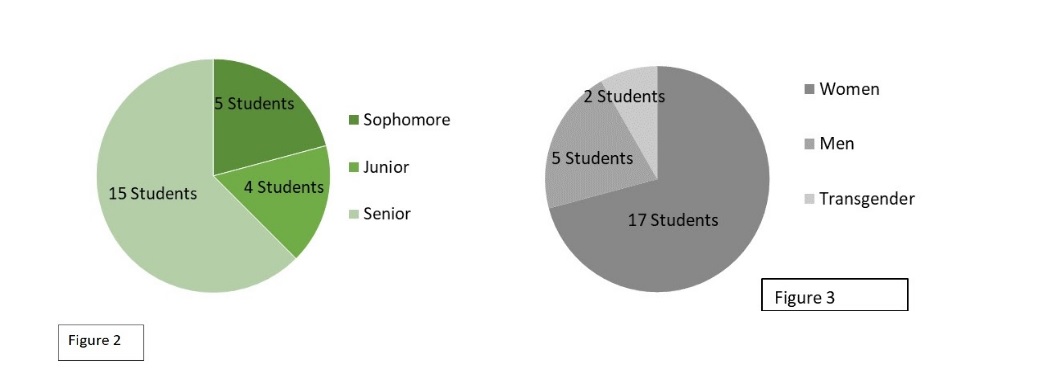

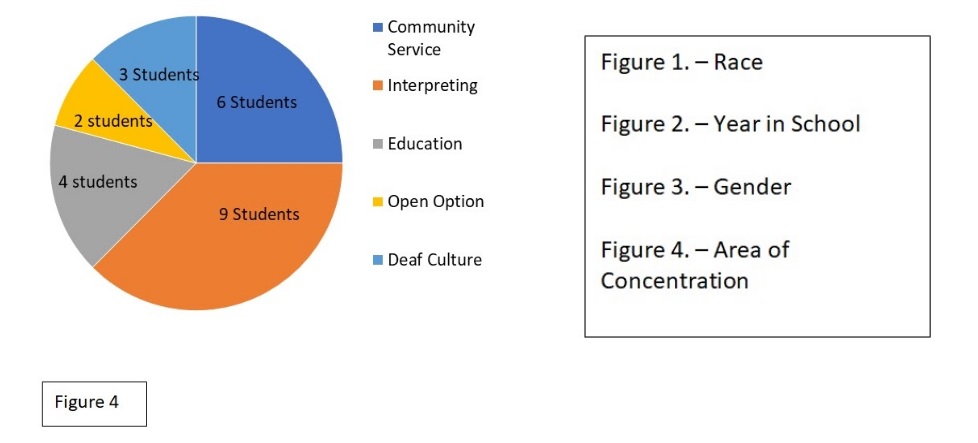

We interviewed 24 participants who met the criteria as 1) students in the Deaf Studies Department at California State University Northridge (CSUN) and 2) self-identified as a “Person of Color.” The purpose of meeting both criteria was to focus our study on the counterstories and narratives of POC who had knowledge of Deaf Studies, the Deaf Community, and CSUN. Interviewing CSUN students exclusively enables a more precise perspective of persons of color in that space. The pie charts below illustrate the data of our participants organized by race, gender, year in school, and area of concentration:

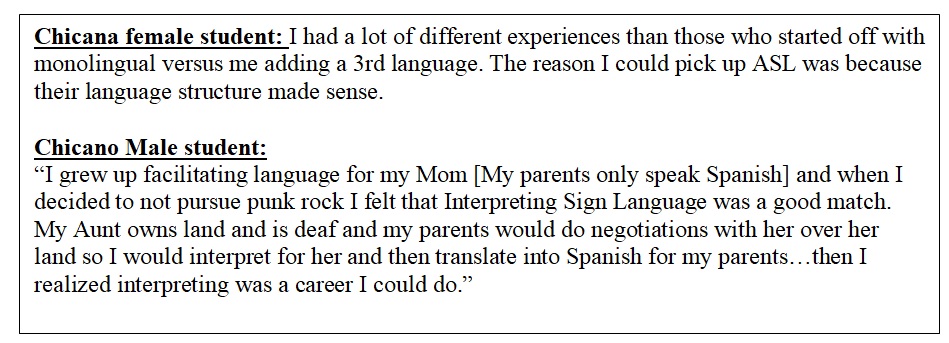

Of our participants, 71% were women, and 63% were graduating students. We would have benefited from a higher percentage of non-graduating students to understand the current mindset of students who are in the process of deciding whether or not to enter the interpreting field. However, by analyzing the experiences of those who graduate from college it allows for an analysis of their personal journey throughout college and their decision to pursue sign language interpreting or not. We had representatives from 6 different racialized minority groups with Black student representation holding the majority at 41%. With 62% of our sample not having a concentration focus of interpreting, we were able to analyze the possible causes and make connections to reasons why the percentage of interpreters of color is so low

Interviews ranged from 45 minutes to two hours depending on participant time constraints. The interview questions dealt with the participant’s family background, educational background, connection to the Deaf community, and career decision-making. All interviews were conducted in spoken English and video recorded. After all, interviews had been conducted, we coded common themes and shared experiences between participants.

Areas of Interest

We noticed that there were very specific, thematic patterns and areas of interest that should be explored more thoroughly. As revealed by the interviews, the data demonstrated the following reasons participants did not pursue interpreting:

- Confidence Issues

- Lack of information about the field

- Limited access to socializing with Deaf communities

- Not a career Interest

- Inability to commit to the time to become an interpreter

The themes that appeared for Deaf Studies students who did pursue interpreting included:

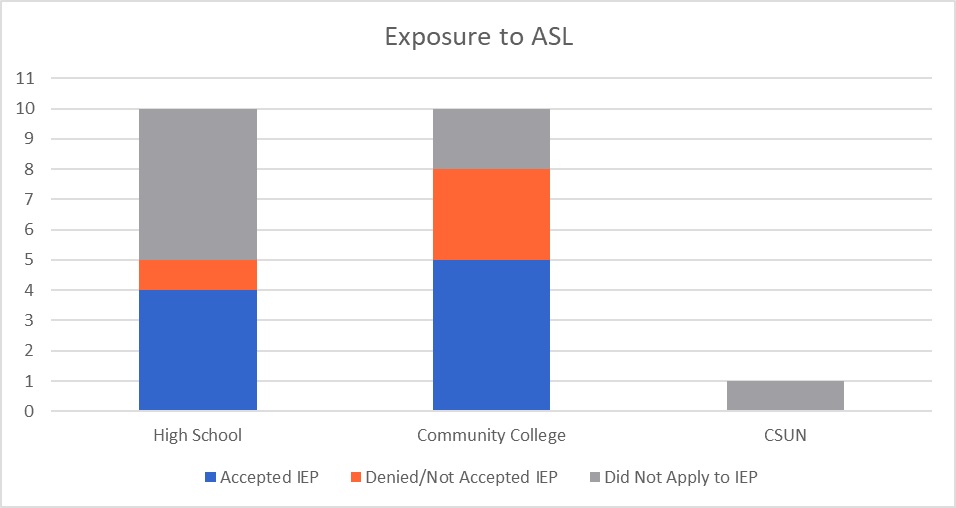

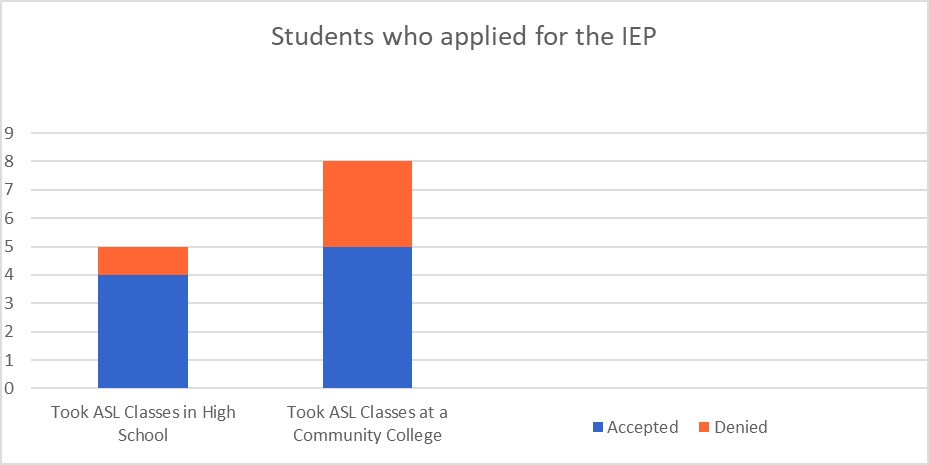

- Access to ASL early

- Spiritual Connection

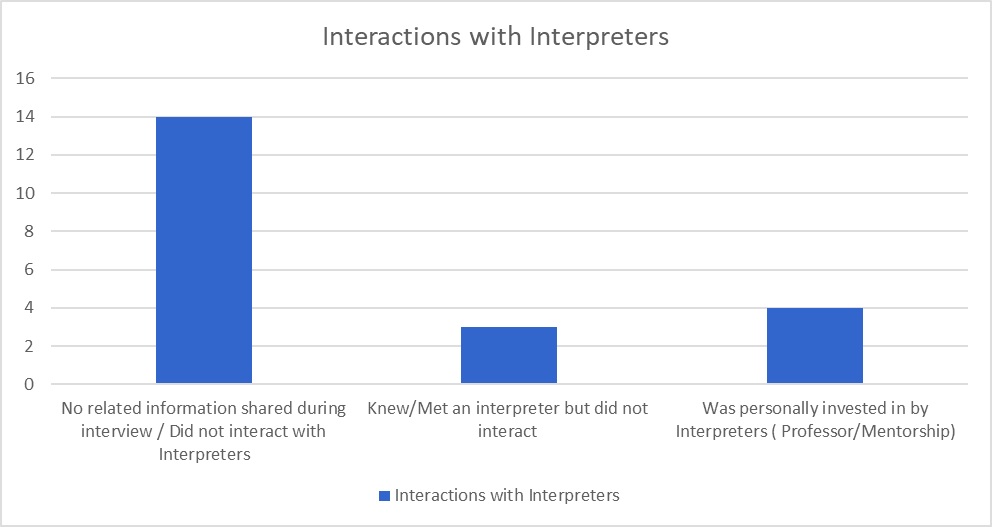

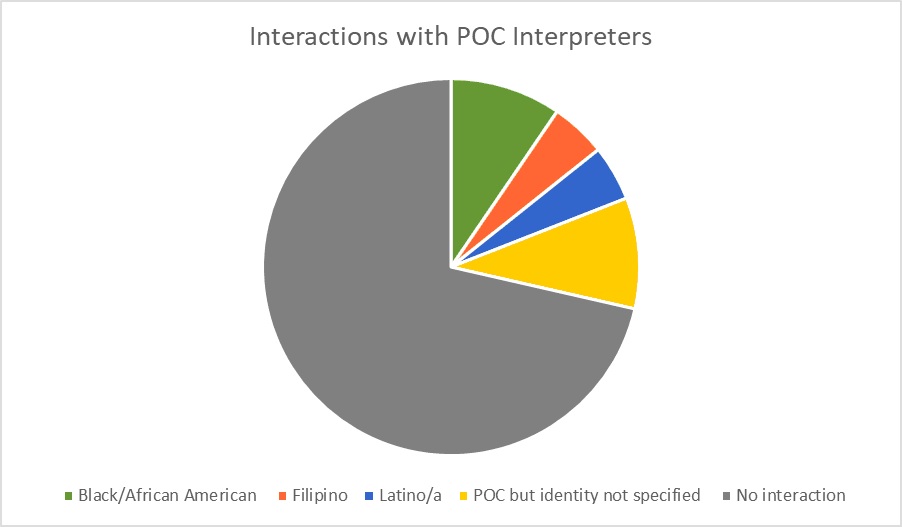

- Mentorship and encouragement

- Not afraid to socialize with Deaf people

- 2nd Language English Learners

Specific themes from our research that will be expanded on in subsequent posts:

This research is critical to the Deaf community as well as the sign language interpreting field because it can act as a catalyst for further research and foster improvements for POC in the interpreting profession. The perspectives of POC within the field of sign language interpreting are not openly discussed. More research and analysis is needed to uncover the issues. We believe that many of the concerns of minority Deaf community members and Interpreters of Color (IOC) are rooted in the current dehumanization of minority groups. This dehumanization stems from a lack of understanding and respect for community knowledge. When this is coupled with the real and perceived barriers caused by the intersection of various forms of oppression, our students opt to pursue options outside of interpreting.

*We would like to thank and acknowledge John Pak, M.Ed., for the time and energy invested in the translation and ASL video work presented here.

References

Delgado, R., Stefancic, J., & Liendo, E. (2012). Critical race theory. New York, NY: New York University Press.

Foster, S., & Kinuthia, W. (2003). Deaf persons of Asian American, Hispanic American, and African American backgrounds: A study of intraindividual diversity and identity. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 8(3), 271-290. doi.org/10.1093/deafed/eng015

Landson–Billings, G. (1995). But that’s just good teaching! The case for culturally relevant pedagogy. Theory to Practice, 34(3). 159-165.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2011). Designing qualitative research (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Parasnis, I. (2012). Diversity and Deaf identity: Implications for personal epistemologies in Deaf education. In P. Paul & D. F. Moores (Eds.), Deaf epistemologies: Multiple perspectives on the acquisition of knowledge (pp. 63-80). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Patel, E. (2016). Intersectionality in Action: A guide for factually and campus leaders for creating inclusive classrooms and institutions. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

Patton, M. (2002). Qualitative research and evaluation methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

West Oyedele, E. (2015). Persistence of African-American/Black signed language interpreters in the United States: The importance of culture and capital [Dissertation].

Witter-Merithew, A., & Johnson, L. (2004). Market disorder within the field of sign language

interpreting: Professionalization implications. Journal of Interpretation, 14, 19-55.

Yosso, T. (2006).The teaching/learning social justice series: Critical race counterstories along the Chicana/Chicano Educational Pipeline. New York, NY: Routledge.

Van Cleve, J., Crouch, B. (1989). A place of their own. Washington, D.C.: Gallaudet University Press

Other Contributors to this Series:

Lissa D. Ramirez-Stapleton

Dr. Lissa D. Ramirez-Stapleton (pronouns: she/her/hers) is an associate professor at California State University Northridge in the Department of Deaf Studies and core faculty for the Educational Leadership and Policy Studies program. Her research focuses on equity and access, identity development, and the educational history of Deaf students, faculty, and staff with a particular interest in the intersections of race, gender, and disability. www.drlissad.com

Jasmine Solis

Jasmine Solis (pronouns: she/her/hers), originally from Orange County California, received her B.A. in Deaf Studies with a concentration in Interpreting from California State University, Northridge (CSUN). As a recipient of the CSUN Presidential Scholarship, Jasmine completed her research unpacking confidence levels and anxiety amongst Students of Color who are currently or planning to pursue interpreting. Now as the full-time Academic Advisor for the Deaf Studies Department at CSUN, Jasmine hopes to continue supporting and encouraging students to reach their career goals.

MJ Jones

MJ Jones (pronouns: they/them/theirs), a Southern California native, currently resides in the Washington, D.C. area. MJ’s intersectionalities include Black, first-generation Filipinx, masculine of center, sighted, and hearing. After graduating from California State University, Northridge with a B.A. in ASL-English Interpreting and a minor in Queer Studies, MJ graduated with their M.A in International Development at Gallaudet University. They are currently an adjunct professor at Gallaudet University and a Full-Time Staff Interpreter with Vital Signs, LLC.