Exposure to ASL and the Deaf community via spiritual settings has been a fraught topic. Lissa Ramirez-Stapleton posits that these arenas may be missed opportunities for attracting People of Color to become sign language interpreters.

“Centuries ago the word vocation, meaning literally “a calling,” applied only to bishops, priests, and monks–those occupying offices within the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church. It was believed that the clergy had been called by God. They alone had a vocation while everyone else merely worked.”

(Jethani, 2013, para. 5)

Introduction

I am often asked how and why I got connected to Deaf studies and what my personal connection is to the Deaf community. People are often looking for some explanation of why a Black hearing woman would ever be interested in the Deaf community unless she had some personal or family connection. I often tell my story of first connecting with the Deaf community as a teenager in a drug prevention teen program which opened the door for me to take American Sign Language in college, which opened another door once I started job searching. Soon the doors continued to open and my life’s work felt less and less driven by me and more orchestrated and planned by something bigger than me. As a spiritual person, who was raised as a holiday churchgoer, who attended Catholic middle school, and who now finds herself open to all forms of faiths and beliefs, I simply tell those curious about my life’s work that I was called. The idea of having a calling as Jethani (2013) states in the above epigraph was historically used by the Roman Catholic church, but in modern times I find that some people are seeking out careers that are more than work. Careers that are fulfilling a greater purpose, that are connected to what they were born to do, and which ignite their passion… a calling.

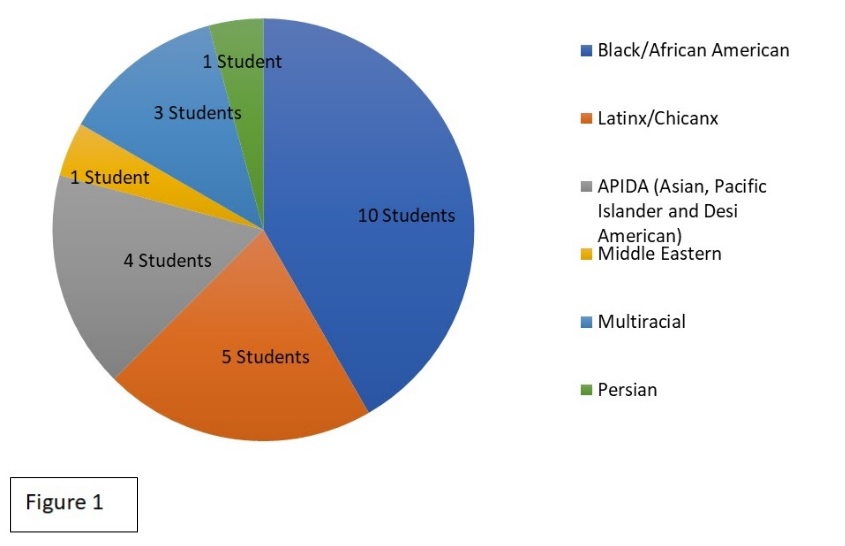

Students of Color find the interpreting field in many different ways, and in our research, one such environment was religion and spiritual spaces. The feeling of wanting to advocate for and with Deaf communities and feeling led into the field by something greater than themselves was an unforeseen outcome. The purpose of this post in our series is to consider the role religion and spiritual spaces play in connecting Students of Color to Deaf communities and ultimately into Interpreter Education Programs (IEP) and the broader interpreting profession.

“Feeling Called”

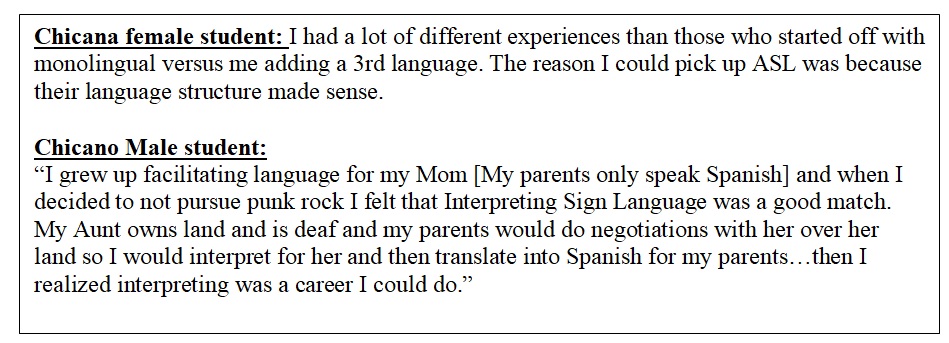

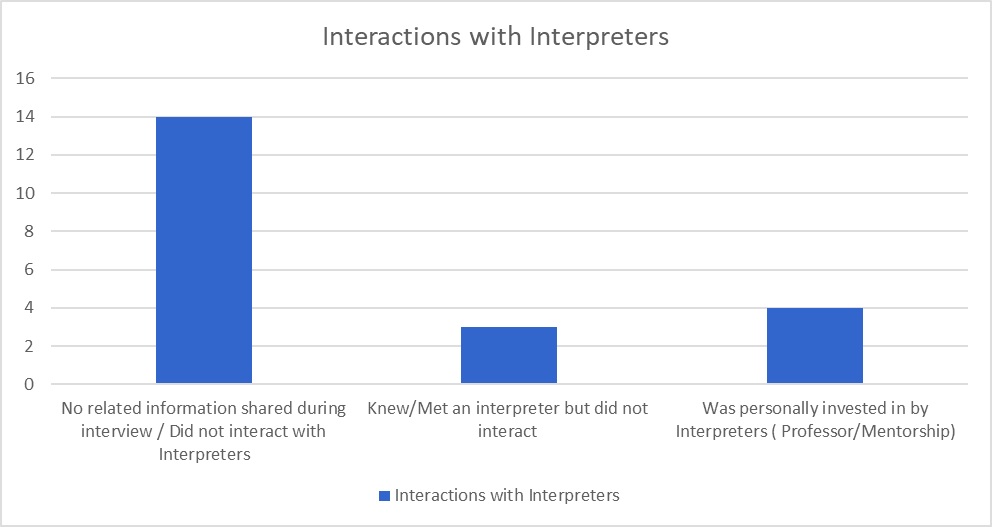

I am not the only person who has felt spiritually led or struggled with the calling to work within and among Deaf communities. Although she lacked confidence in her signing and sometimes wanted to give up, one Afro Latina student still felt led to work within the Deaf community. She said, “I just feel a calling to this field. I’ve been praying about it and I feel led.” This spiritual connection allowed her to be creative with her major, leading her to combine Deaf studies with a health field and to keep enrolling in signing classes even though she did not always feel confident in her ability. She often shared that she was highly encouraged by other Deaf People of Color to keep pursuing her goals.

I also asked the Interpreters of Color on the Reality of Interpreting: Interpreters of Color Facebook page (ROI) what they thought about the topic. One person said, “Church WAS my ITP [Interpreter Training Program],” and further explained,

I know that a “calling” is a starting place. In the Christian tradition, there is a calling and there is preparation and there is growth. I was blessed to have these over a number of years that let me walk right into a new profession but again I was mentored by professional Deaf and hearing mentors from the very beginning.

For some Students of Color, their first exposure to Deaf communities is through Deaf ministries or Deaf community members. A Latina student said “My Godmother invited my family to her church and they have a Deaf ministry. I got involved with the ASL choir, took ASL 1 and we had a Deaf preacher.” The support, encouragement, and relationship building occurring for Students of Color in spiritual spaces helps them persist in the field despite self-doubt. These spiritual spaces also provide safer places to practice, connect, and enter into Deaf culture.

Interpreters Raised in Spiritual Spaces

It is also important to consider the type of skills and exposure Students of Color coming out of spiritual spaces are getting that may be helpful to them as future interpreters as well as experiences that may be harmful and must be addressed.

In-depth Community Exposure

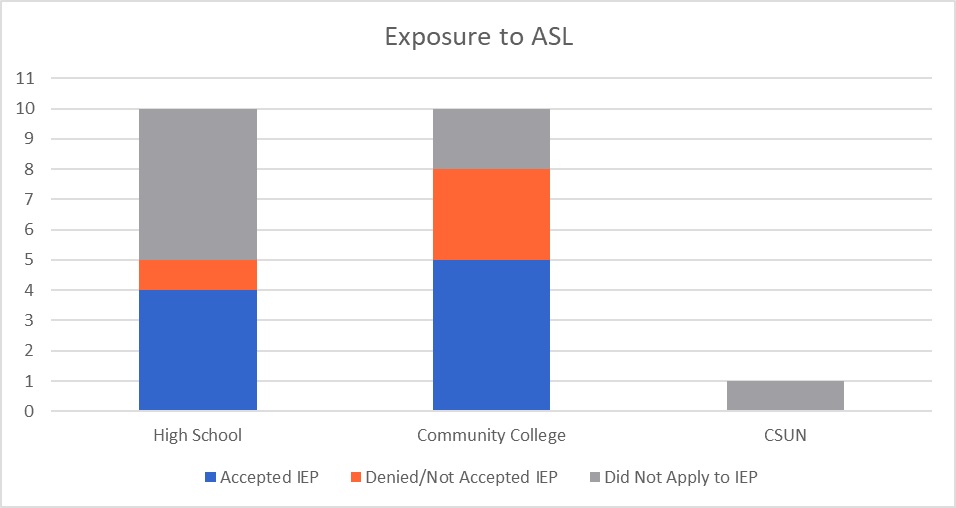

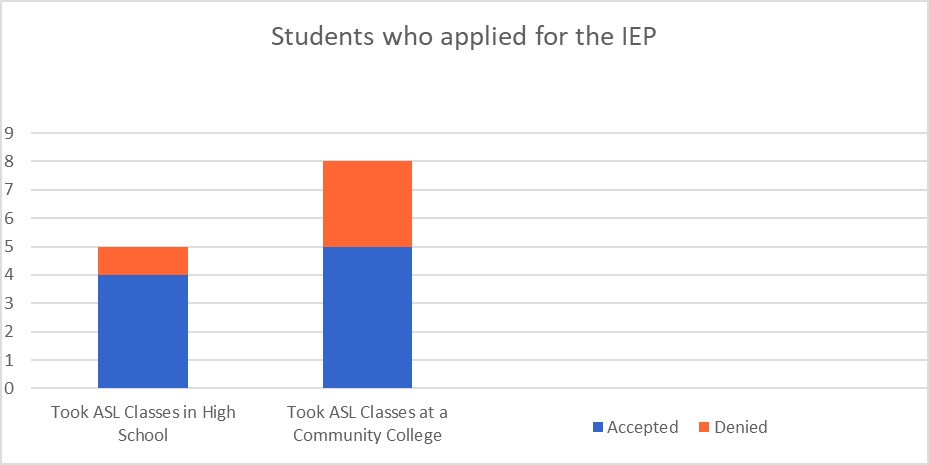

Students of Color who come from spiritual spaces have immediate and one-on-one exposure to Deaf people, culture, and language. A Black female student said, “My junior year in high school, we got a new pastor and his son is Deaf…he encouraged me to learn sign language, so I started my junior year.” This is important as our research shows that the earlier students are exposed to ASL, the more likely they are to be accepted and complete an IEP (see Blog 2 of the series). Students of Color from these spaces are also more likely to interact with people who have different signing abilities as stated by this Interpreter of Color from ROI,

The Deaf ministry had a wide spectrum of ASL users. This meant that for almost every event, I had to alter my target language… It was an amazing opportunity to be able to practice this skill.

These opportunities can be very positive and uplifting when mentorship is given and one’s skills match the job, but there are some cases where inexperienced signers are thrown into overwhelming and inappropriate interpreting situations that are unethical and damaging. Limited budget or volunteer-based programs should not take advantage of budding sign language interpreters. These are moments that some Students of Color walk away from feeling discouraged. One Latina student said the interpreter didn’t show up for church, so a Deaf friend asked her to step in. She left the experience feeling very stressed and tearful. Another Latino student said he would never be an interpreter because of a loss of confidence he felt after he was put into an inappropriate interpreting experience.

Addressing Contradicting and Challenging Topics Early On

Some Students of Color may feel led to work with the Deaf community, but because of their own experiences with oppression and marginalization, they struggle with the contradiction between what they value and how the field works. For example, a Middle Eastern Latina student said,

I don’t want to be an interpreter because I remember hearing that as an interpreter…If there’s something unkind being said… you don’t get to advocate and that is not me. I’m not going to sit there and keep my mouth shut.

Some Students of Color who are exposed to spiritual space interpreting get exposed to these conflicts early on and find ways to reflect and maneuver around them. An interpreter from ROI stated,

There were times where hot topics would come up in a sermon, and I had to interpret true to the speaker, even if I had disagreed. I was able to do so…but later on, I would have to deal with the emotions of that.

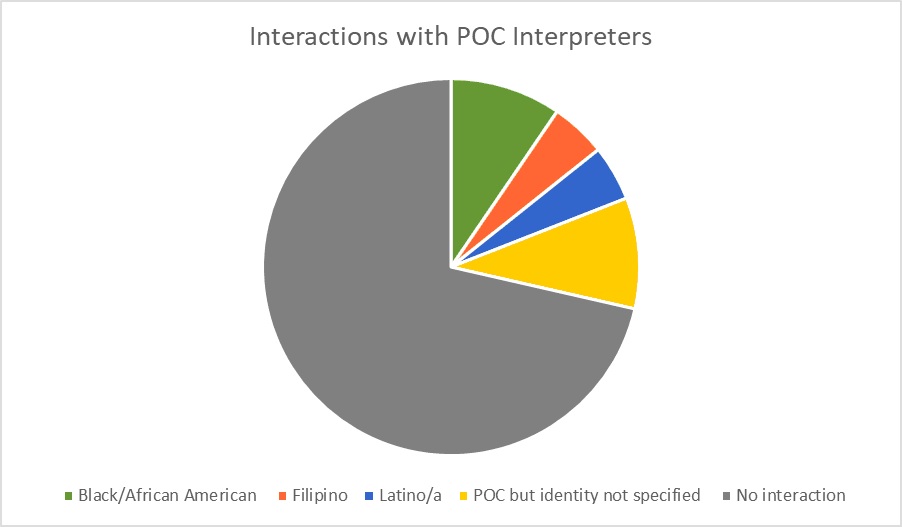

This interpreter, through mentorship, found ways to work through this challenge. However, I would like us to ponder bigger questions of the Deaf and interpreting community. What does it mean to be a social justice advocate and a sign language interpreter? Is it always a conflict of interest? Are there different ways for sign language interpreters to address issues without overstepping their boundaries? If our oppression is interconnected, then we must collectively fight to end all forms of oppression. Because many Students of Color understand oppression from a specific perspective, the idea of “neutrality” may keep them out of the field and the larger fight for Deaf equity.

Learned Audist Spiritual Undertones

I know spiritual and religious motivations for working with the Deaf community, particularly through missionary work, have historically had and still could have, some audist undertones of “helping” Deaf communities, which has not been empowering, respectful or mutual. Another Interpreter of Color from the ROI page stated:

I often find myself in conversations with hearing folk (non-signers) where they are praising me for doing God’s work. The mentality often was that I was amazing for caring for the Deaf…I understand that they meant well…I wasn’t helping hearing-impaired people to keep up with the world. I was literally interpreting one language to another.

As a Deaf Studies teacher, I see these sentiments often with students, those who come from spiritual spaces, and those who do not. In all of our IEP and Deaf studies programs, we must address the idea of “help” and the ways in which it can be patronizing as well as how we should all embrace interdependence and support. This is something in which to continue to be mindful and proactive.

One Calling Doesn’t Fit All!

For some students, calling or no calling, there are obstacles that still interfere with them being able to complete a program. One Latino student said, “I’m on ROTC scholarship. I have to graduate in a specific time, and I’d need another year to do the interpreting program.” For other students, something shifts for them. A Filipino/Mexican student initially felt led to interpreting and was highly supported by peers and teachers, but realized with all the pressure to become an interpreter, he misread his passion. He stated,

During my second semester at RIT, my professor asked us all to close our eyes and imagine us waking up and she asked us where we all were going…and of course, we were supposed to respond [and say] to an interpreting assignment and I realized nope that [interpreting] is not where I am going.

IEP instructors, Deaf Studies faculty, and the greater Deaf community can help Students of Color stay connected through other career fields within the Deaf community because as this student said, “I realized that there are other things I can do with the Deaf population that appealed to me being an advocate.” Deaf Communities of Color and the broader Deaf Community have a need for People of Color in all aspects of Deaf life, including education, social work, counseling, and many other fields.

Conclusion

Where and how Students of Color are exposed to the Deaf community varies. It requires educators, interpreters, IEP coordinators, and Deaf community members to seek out culturally rich environments as well as participate in active and intentional recruitment of Students of Color. It also requires us to create and nurture authentic spaces for the growth and development of language skills, cultural knowledge, and the confidence to move within signing spaces.

So where do we go from here? What questions might we consider moving forward?

- Are your students first exposed to Deaf communities and American Sign Language within a religious and spiritual space? If so, from where? If not, is there a possibility to open those lines of communication and connection?

- Many IEP programs are at public institutions. What challenges might you face connecting to religious or spiritual spaces? How might you work through them versus avoiding the possible relationship?

- How does the topic of religion and spirituality influence Deaf Students of Color and the interpreting field? Are these places we might consider as pools to increase our certified Deaf Interpreters of Color?

- This piece has Christian undertones. What might an intentional interfaith approach to Students of Color IEP recruitment look like?

- Most of the participants that had a spiritual connection were self-identified women. What might it mean for self-identified men or trans/non-binary folks and their exposure to Deaf culture and communities?

*We would like to thank and acknowledge Felicia Williams, for the time and energy invested in the translation and ASL video work presented here.

Reference

Jethani, S. (2013). Uncommon callings: To reach a new generation, we must affirm not just God’s general callings but people’s specific callings. Leadership Journal, 34(1).

Other Contributors to this Series:

Will Garrow

Dr. Will Garrow, Ph.D. (pronouns: he/him/his) is from upstate New York, where he was first introduced to the Deaf Community through his career as a professional snowboarder. All of his degrees are from Gallaudet University with a Bachelor of Arts in Deaf Studies, a Master of Arts in Linguistics, and a doctorate in Linguistics. As a faculty member at California State University, Northridge, his teaching mainly focuses on how oppression works in American society, Deaf Culture, and ASL Linguistics. When Will is not teaching, he can be found either on the snow in the mountains or splatting balls in the racquetball court.

Jasmine Solis

Jasmine Solis (pronouns: she/her/hers), originally from Orange County California, received her B.A. in Deaf Studies with a concentration in Interpreting from California State University, Northridge (CSUN). As a recipient of the CSUN Presidential Scholarship, Jasmine completed her research unpacking confidence levels and anxiety amongst Students of Color who are currently or planning to pursue interpreting. Now as the full-time Academic Advisor for the Deaf Studies Department at CSUN, Jasmine hopes to continue supporting and encouraging students to reach their career goals.

MJ Jones

MJ Jones (pronouns: they/them/theirs), a Southern California native, currently resides in the Washington, D.C. area. MJ’s intersectionalities include Black, first-generation Filipinx, masculine of center, sighted, and hearing. After graduating from California State University, Northridge with a B.A. in ASL-English Interpreting and a minor in Queer Studies, MJ graduated with their M.A in International Development at Gallaudet University. They are currently an adjunct professor at Gallaudet University and a Full-Time Staff Interpreter with Vital Signs, LLC.