The transition from student to working interpreter can be challenging when current practitioners are hesitant to step forward as guides. Brian Morrison pushes back on some negative mindsets regarding passing the torch, and makes suggestions on how to reach out to the next generation.

With fall upon us, students in interpreter training programs all over the country have begun another semester on their journey to becoming a sign language interpreter. Along with the classroom lectures and hands-on practice teachers are planning, they are also reaching out to the interpreting community for one of the most crucial pieces of the students’ development, observation and mentoring opportunities. However, these opportunities are becoming increasingly difficult to find. While some of the scarcity can be attributed to specific requirements of the situation, some of the difficulty is also due to a lack of support by the sign language interpreting community.

“Why would I train students to take my jobs?”

The statement above is a common one given as an explanation as to why sign language interpreters don’t want to work with students. This statement saddens me not only as an interpreter, but as an interpreter educator as well. Personally, I wouldn’t have achieved what I have today if it wasn’t for the mentors and interpreters that I looked up to and served as models during my early development. As an educator who is striving to find opportunities for students, it’s equally frustrating.

How many of us benefited from these types of relationships that our students are striving to find and often cannot? What if, while we were developing our own skills, interpreters had given us the same reply? Would we be the interpreters we are today?

Where’s the disconnect? All interpreters who have gone through an Interpreter Education Program (IEP) experienced similar requirements for working with interpreters as students are doing now. Has it been so long that we’ve forgotten what it was once like when we were in their shoes?

Overall, students in these programs truly want to become interpreters and be contributing members of the profession. They sacrifice their time to focus on their skills and are committed to that process. As Stacey Webb highlights in her article, The Value of Networking for the Developing Sign Language Interpreter:

“In order for students to be successful sign-language interpreters, prior to graduating it is critical that they develop a relationship with both the Deaf and Hard of Hearing Community (DHHC) and current-working professionals within the DHHC. This would include interpreters, educators and DHHC advocates. By fostering these relationships, students will create educational, professional and personal opportunities that would not be available to them outside of the classroom environment.”

So while students do make attempts at networking to cultivate these opportunities, it is very often a struggle.

“They have no respect for the elders in the profession”

This statement above, and variations of it, is another common sentiment towards students. While I don’t deny that attitudes reflective of this statement do exist among students, I also have to wonder how much responsibility can be attributed to the current state of the ‘system’? What I have learned is that students are very observant. They learn by watching and they often emulate what they see. In our reluctance to work with students, have we conveyed to them that we don’t value them or their work? Have we somehow systematically disrespected the label “student” through our actions or lack thereof? In her article, What Role Does Civility Play in the Sign Language Interpreting Profession?, Carolyn Ball stresses the importance of civility in the field of interpreting and interpreter education. She states:

“If all interpreters, educated through formal training, were given a clear sense of the importance of civility in the workplace and in interactions with colleagues, perhaps more recent graduates would benefit from repeat business and high levels of job satisfaction.”

As educators, cultivating an attitude of civility is definitely something that we can incorporate into our interpreter education programs. In turn, as experienced interpreters, we can also be the models of civility that we want them to emulate by embracing these students and guiding them into the profession.

As a profession, we recognize there is a shortage of qualified sign language interpreters. While several factors contribute to this, the fact is that most of these graduates will go on to work as interpreters. Many of them, like most of us when we started working as interpreters, will not be as prepared as they should be. Additionally, at some point, they will become our colleagues. If, as a profession, we made a commitment to being more involved with students early on in their professional lives, we could be training the team member we will want to work successfully with later. The latter scenario also suggests apossibility, the interpreted interaction as much more successful.

“I can’t believe you don’t know that!”

Interpreter education programs have a finite amount of time. We know that they aren’t able to teach everything we would like students to know before they enter the field. The field of sign language interpreter education has grown in the last several years thanks to organizations such as the Conference of Interpreter Trainers (CIT), the Commission on Collegiate Interpreter Education (CCIE), and National Consortium of Interpreter Education Centers (NCIEC). New research, new curricula, and improved standards for education programs are now available and these programs have access to materials and information which weren’t previously available. Rather than viewing interpreter education programs negatively or putting the sole onus on them for having not taught students all they need to know, we can shift our focus to building on their existing foundation. To echo Kate Block’s sentiment in her article, Mentorship: Sign Language Interpreters Embrace Your Elders, take advantage of this new information that the students can bring to our work. Imagine the outcomes when the new student and the experienced interpreter learn and grow from sharing their knowledge with each other.

“What can I do?

I think first and foremost, we can be the manifestation of the theme, “I Am Change”, as StreetLeverage challenges us to do through this website. Interpreter education programs and students cannot be ignored, so as a responsibility to our profession, we can decide to step up and support our novices.

How can we make that change? There are several things that as individuals we can do right now.

Remember your passion.

Reflect back on your journey to becoming an interpreter. Remember what it was like to be that student…eager to learn and wanting experiences.

Offer observation.

Offer 2-3 opportunities a month to the local ITP for student observations. While much of the work may not be suitable or possible to have students present, we often do have situations that would be perfect.

Present.

Offer to go and speak to students at the local ITP. If you can’t offer them observations, offer them your wisdom in the classroom.

Sponsor a student.

Become a “Big Brother/Big Sister” to an ITP student. I think if we all look back to our early days, at least one name will come to mind as someone who “took us under their wing” and got us through. Be that person to a student. Be the interpreter you want to see the students grow to become.

Host an induction.

As a community and/or alumni association, host an induction ceremony for a graduating group of interpreting students. Acknowledge their hard work and dedication while welcoming them into this sometimes crazy, always wonderful world of interpreting.

Start a group.

Establish reflective practitioner groups that include students and new interpreters. StreetLeverage articles provide excellent discussion material for all levels of sign language interpreters. Case conferencing allows for insightful discussions of the decision making process based on actual scenarios.

I’m a strong believer in the idea of “it takes a village.” This is our profession and as such, we need to actively commit to the next generation of interpreters. Let’s face it, as individuals we will not be in the field forever. In order to preserve our legacy, we can leave positive impressions on the lives of the next generation. Let’s raise them well.

What will your contribution be?

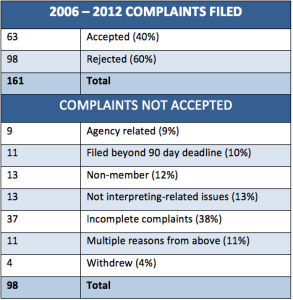

As part of the commitment to the EPS program, the EPS staff has begun compiling data to help facilitate informed dialogue. The data compiled here reflects the years following the adoption of the CPC in 2005.

As part of the commitment to the EPS program, the EPS staff has begun compiling data to help facilitate informed dialogue. The data compiled here reflects the years following the adoption of the CPC in 2005. RID utilizes a grievance system that includes a punitive component and also encourages communication, mediation, the resolution of conflict with a rebuilding of trust and confidence. This process is designed to be both corrective and educational in nature.

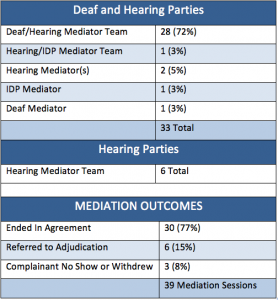

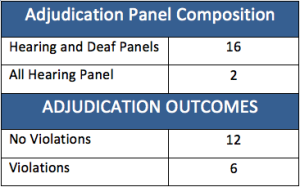

RID utilizes a grievance system that includes a punitive component and also encourages communication, mediation, the resolution of conflict with a rebuilding of trust and confidence. This process is designed to be both corrective and educational in nature. To date, there has been no formal study on the correlation between failed mediations and violations at adjudication. This may be a necessary step to assess the effectiveness of the program, examining whether the adjudication phase lacks rigor. Another possibility is that those cases that do not end in mutual agreement at mediation might be where the parties remain at odds and the interpreter is confident that his/her actions were in compliance with the CPC.People have asked why so few violations are published in VIEWS. Most cases do not go beyond mediation because both parties voluntarily agree to and embrace their resolution to the situation. While some might prefer to see more sign language interpreters brought before a jury of peers, the philosophy behind the RID mediation program has always been that the parties should be actively engaged in the EPS process, which often starts with mediation.

To date, there has been no formal study on the correlation between failed mediations and violations at adjudication. This may be a necessary step to assess the effectiveness of the program, examining whether the adjudication phase lacks rigor. Another possibility is that those cases that do not end in mutual agreement at mediation might be where the parties remain at odds and the interpreter is confident that his/her actions were in compliance with the CPC.People have asked why so few violations are published in VIEWS. Most cases do not go beyond mediation because both parties voluntarily agree to and embrace their resolution to the situation. While some might prefer to see more sign language interpreters brought before a jury of peers, the philosophy behind the RID mediation program has always been that the parties should be actively engaged in the EPS process, which often starts with mediation.