In search of the “Reasonable Interpreter Standard”… Re-thinking the NAD-RID Code of Professional Conduct with a fresh look at current best practices, recognition of role-space, advocacy and social media ethics.

Hurray! The RID Code of Professional Conduct Review Committee report came out on 6/23/2015! Many of us are eagerly awaiting a revised CPC. After reading through it, I felt inspired to sit down and draft a document which constitutes my approach to the intricacies of ethical practice, both philosophically and pragmatically, in my daily community sign language interpreting work.

[Click to view post in ASL]

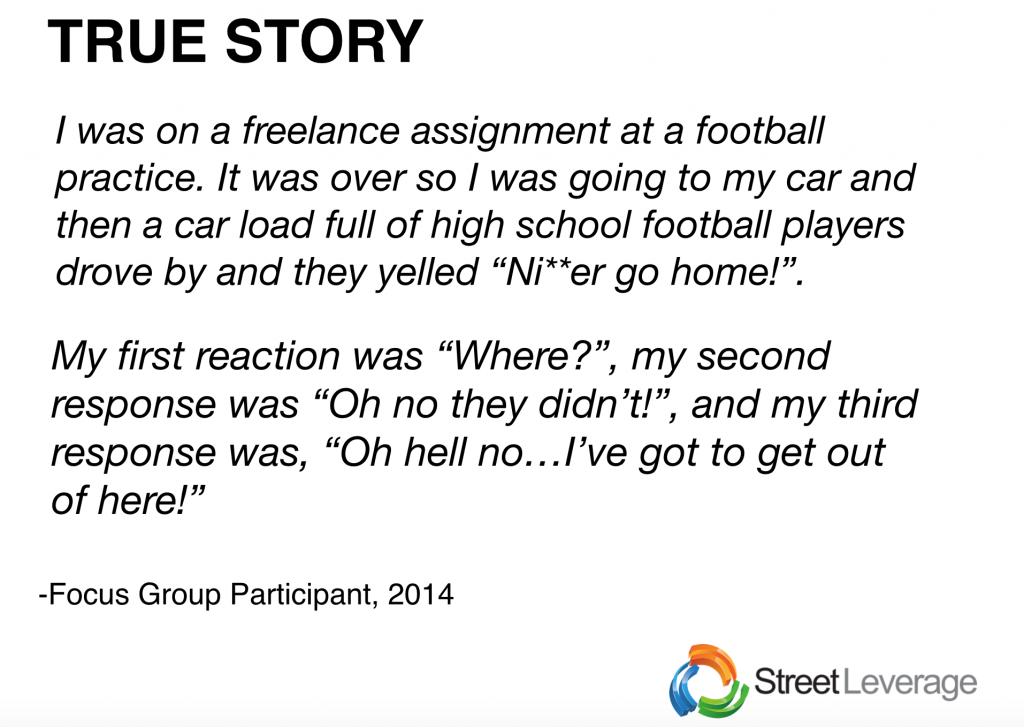

This proposed draft is the fruit of fantastic input from a variety of sources (listed below) and also from the sometimes painful juxtaposition of the perceived proper role of a professional interpreter and an outdated CPC. As an interpreter who works for a variety of agencies and entities over a large geographic area, this proposed CPC is more compatible with my collective experiences over the past 26 years as an ASL interpreting practitioner and attempts to address many of the concerns raised in the recent CPC Review Committee report.

Your input and perspectives are invaluable! Share your thoughts on this important topic that has far reaching implications for individual interpreters and the community at large.

Thank you!

Code of Professional Conduct for ASL Interpreters (DRAFT)

Preamble

Interpreting is an art and service profession. Interpreters work to provide access for individuals who do not share a common language or language mode. To demonstrate their commitment to the technical as well as relational components of the work to remove language barriers, respect cultural norms and promote shared communication, RID Certified American Sign Language Interpreters shall adhere to the following professional standards that both guide interpreter conduct and protect the public trust in certified interpreters.

Applicability

All RID Certified Interpreters are bound to comply with this Code of Ethics. Interpreting students and interns are encouraged to adhere to this Code as pre-professionals, in conjunction with supervision by RID Certified interpreters, mentors and instructors.

Tenets

1. Accurate and Complete Interpretation

Each participant’s source language should be faithfully rendered in a manner that conserves and conveys all meaningful elements of the speaker’s message and intent into the target language. A natural prosody that reflects the tone, style and register of the speaker should be employed. The interpreter shall strive for the highest standards of accuracy to enable the parties to clearly communicate with one another and avoid misunderstandings. The interpreter shall make repairs promptly and discreetly. If at any point an interpreter is unable to fulfill this tenet, the interpreter has a duty to either decline or remove her/himself from the assignment. Sight translation of forms and documents is within the scope of practice. Consecutive, simultaneous, team or relay interpreting with an intermediary interpreter are all valid approaches to this task, and the interpreter shall use professional discernment to request a team interpreter to effectuate communication.

2. Commitment to Autonomy

The interpreter shall constantly strive to support full autonomy of the participants. While some situations may require the interpreter to make adjustments such as improved positioning, lighting or other logistical considerations, the primary focus will be to facilitate participant autonomy. The interpreter shall avoid interjecting actively into the conversation or message. Exceptions include utterances which constitute social pleasantries, responding to direct questions, management of the interpreted interaction such as checking in with the parties to ensure the interpretation is clearly conveyed and accessible, clarification of content and professional courtesies. Interpretation is a group activity creating a shared experience, and the interpreter has a duty to interact in ways that are socially responsive, culturally and linguistically inclusive and also maintain an overarching commitment to participant autonomy.

3. Confidentiality

Privileged or confidential information acquired in the course of interpreting or preparing for an assignment shall not be disclosed by the interpreter without authorization. Data and records shall be handled using current industry standards including password protected computer files, locked cabinets and shredding of obsolete documents. HIPAA laws or any other federal, state or local laws governing information management shall be adhered to strictly. Interpreters work in a variety of settings for a variety of entities. Case studies, which are representative of repeated occurrences within interpreted interactions over time, can be shared with peers for the purpose of analysis and professional development in the same manner that other professionals conduct continuing education with the goal of improved service outcomes. Interpreters may make public comment on public information.

4. Professional Demeanor

Interpreters shall conduct themselves in a professional manner that engenders respect for all parties. This applies to standards of dress which are conducive to a visually accessible interpretation. For most interactions business casual is appropriate. Identification such as a badge is recommended to assist the parties in readily identifying the working interpreter. Examples of professional conduct include prompt confirmation of availability, fulfillment of confirmed assignments and punctuality. The interpreter shall maintain appropriate professional boundaries and separate personal from work interactions out of respect for all parties. Social media shall be used judiciously with consideration for all parties with particular attention to maintenance of standards of confidentiality. Obtain permission from all parties before posting shared experiences on social media or online.

5. Collegiality

Interpreters shall strive to work effectively, professionally and in good faith with all colleagues, mentoring partners, interpreting interns and students. Team interpreters shall caucus as needed before, during and post-assignment to ensure an optimal interpretation. Colleagues shall be approached directly, privately, one-on-one, to address any concerns or breaches of ethical conduct. Filing of grievances shall be made only after all other standard conflict resolution methods have been unsuccessful. Every effort shall be made to maintain open, accountable and positive relationships with peers that support full communication access for all parties.

6. Preparation

Interpreters shall make all necessary efforts to prepare adequately for assignments. This includes obtaining preparation materials such as speeches, meeting agendas, documents, textbooks, police reports, etc., that will promote the most complete and accurate interpretation.

7. Conflicts of Interest and Role-Space

Interpreters shall avoid conflicts of interest and dual roles which result in diminished capacity to devote full attention to the task of interpreting. The concept of a conflict of interest is well established, and interpreters shall adhere to norms of conflict of interest avoidance, both perceived and actual. Unanticipated conflicts of interest shall be disclosed to the parties promptly. Complete neutrality, or the absence of vested interest is not achievable. Interpreters are dedicated to effective communication for all parties. However, interpreters can commit to fully participate in the role-space of interpreter to facilitate communication in order to support the parties in reaching their mutual goals of shared exchange.

8. Professional Development

Interpreters shall maintain RID certification, completing required CEUs within each cycle, and also engage in supplemental continuing education, mentoring, pro-bono work, etc., to promote the furtherance of knowledge and skills within a framework of social justice. Membership and participation in professional organizations is strongly encouraged.

9. Advocacy and Resource Referral

Interpreters are in a unique position as functional bi-cultural bilinguals. Interpreters shall provide referrals to available and appropriate community resources to support equal access. Interpreters may engage in advocacy services in settings that are separate from the interpreting function and that fall within standards of acceptable professional conduct and do not constitute a conflict of interest.

10. Functional Maintenance

Interpreting is physically, emotionally and mentally demanding. Interpreters shall make reasonable efforts to ensure that all members of the interpreting team have adequate supports, including breaks, to promote health and longevity in the interpreting field. Interpreters shall decline or discontinue assignments if working conditions are not safe, healthy or conducive to interpreting.

11. Business Practices

Interpreters shall adhere to the highest standards of ethical business practices which include but are not limited to accurate invoicing, charging reasonable fees for services rendered which constitute a livable wage, payment of taxes, maintenance of licenses and professional liability insurance, etc. Interpreters shall engage in pro-bono interpreting. Interpreters shall refrain from using confidential interpreted information for personal, monetary or professional gain or for the benefit or gain of personal or professional affiliations or entities. Interpreters shall avoid interpreting in settings which involve payment terms that are inconsistent with the Americans with Disabilities Act or any other federal or state law or local statute prohibiting discrimination.

12. RID ED: K-12

RID Certified ED: K-12 interpreters shall adhere to the most current version of the EIPA Guidelines of Professional Conduct for Educational Interpreters when working in K-12 educational settings.

13. Court Certified Interpreters

Legal interpreters have an additional level of ethical accountability to the courts and judicial system. Interpreters qualified to work in legal settings by either federal or state regulations or by virtue of RID legal credentialing shall prioritize the applicable court interpreter oath and timely access to due process. Legal interpreters shall strive to comply with current best practices and make statements on the record, requests, disclosures and recommendations that represent current best practices for legal interpreters.

14. Adherence to Federal, State and Local Law

Interpreters shall abide by all federal, state and local laws which supersede this Code of Professional Conduct. Interpreters shall fulfill all mandatory reporting duties and respond to subpoenas.

Reasonable Interpreter Standard

No illustrative behaviors are included. All tenets shall be considered using the reasonable professional interpreter standard. If an action, engaged in repeatedly, would promote:

- increased autonomy of the parties

- effective communication exchanges

- encourage public trust in the interpreter’s services

by actions taken in good faith effort adherence to these core tenets, the behavior should characterize that of a reasonable professional interpreter. For further assistance, please contact the RID Ethics Committee.

Questions for Consideration:

- Forget about dream vacations…What is your dream CPC?

- How do you want to see social media addressed collectively?

- Why is a succinct CPC preferable to a 5 page test-prep document?

References:

Llewellyn-Jones, P. & R.G. Lee (2014) Redefining the Role of the Community interpreter: The concept of role-space. Carlton-le-Moorland, UK: SLI Press.

National Association of Judiciary Interpreters and Translators.

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Inc.

EIPA: Guidelines for Professional Conduct

Dean, R. K., & Pollard, R. Q (2011). Context-based ethical reasoning in interpreting: A demand control schema perspective. Interpreter and Translator Trainer, 5(1), 155-182.

Collegial Assistance:

Thank you to Xenia Woods, along with the Street Leverage staff, for their willingness to review and provide feedback and edits on this submission! Thank you also to Mr. Ed Alletto for his insightful legal trainings and gentle but direct prompting.

Footnotes:

Q: Why aren’t there any definitions?

A: Unnecessary as this applies to the RID Certified Interpreters.

Q: Why not include the section about “representing qualifications accurately”?

A: Because it is already illegal to misrepresent yourself and this CPC only applies to RID Certified Interpreters

Q: Why not address VRI/VRS?

A: Unnecessary as this applies to RID Certified interpreters regardless of venue. Employment requirements are separate from a Code of Professional Conduct, which applies to members of a professional group.

Q: Why not more illustrative behaviors?

A: A CPC should be succinct. This covers the core tenets and should be interpreted using the reasonable interpreter standard, which this version makes more explicit and should strengthen the application of this CPC. It is not possible to list all applicable illustrative behaviors. It is possible to provide ethical principles with guidelines for making determinations that will result in ethical conduct. See Model Code of Professional Responsibility for Interpreters in the Judiciary for an example of this format.

Q: Why not discuss the Demand Control Schema?

A: In my opinion, DCS is a is a tool used to manage the interpreting interactions, but is not appropriate in a CPC. Individuals can engage in behaviors that do not match up with the CPC, and then state a need to use certain controls because of demands that are the result of earlier poor choices that could have been avoided. The CPC should stand above the DCS, which then can be used to comply with the CPC. [Edit 8/6/15.]

Q: Why not include a separate tenet for medical interpreters?

A: This may be necessary at a future date if a separate medical certification is added by RID. At the moment this CPC along with HIPAA laws and contracting terms provide sufficient ethical guidance. (For example: no unsupervised access to clients, and stepping out of exam rooms when patients need additional privacy.)

Q: Why not make this binding for students/interns?

A: The CPC can only be binding for certified members, who can participate in grievance procedures, be sanctioned and have their professional certifications suspended or revoked. Students may, for example, have a course requirement to adhere to the CPC in order to participate in an internship placement, but do not have a professional duty to adhere to the CPC until achieving certified status. The number of non-RID certified interpreters working in the field continues to decline, as states adopt requirements for licensure that are predicated upon RID certification. The onus is on the RID Certified interpreter to guide the student/intern to adhere to the CPC. See the ABA Model Rules for Professional Conduct Rule 5.3 for an example of this supervisory relationship.

As the noise of Bourbon Street fades to allow a framing of the developments at the 2015 RID conference held August 8-12th in New Orleans, LA, questions linger regarding the suspension of performance testing. With some time and the visibility sought from the results of the risk assessment expected in November, we hope for greater clarity for the path forward. For more coverage on the credentialing moratorium click

As the noise of Bourbon Street fades to allow a framing of the developments at the 2015 RID conference held August 8-12th in New Orleans, LA, questions linger regarding the suspension of performance testing. With some time and the visibility sought from the results of the risk assessment expected in November, we hope for greater clarity for the path forward. For more coverage on the credentialing moratorium click