How can sign language interpreters in the United States help to improve the quality of sign language interpreting services internationally? Debra Russell provides information and suggestions for getting involved locally to have a global impact.

What is the role of sign language interpreters in supporting other interpreters in other countries, and what strategies can reinforce Deaf community and interpreter collaborative work?

As President of the World Association of Sign Language Interpreters (WASLI), I am often asked these questions, as well as why I chose to be part of an international organization. Being part of the development of WASLI has been an incredible experience filled with opportunities to work with, and learn from, other volunteer board members from every region of the world. The association in its short six years has been able to create a network of interpreters throughout many countries, and we have tried to model collaboration between Deaf associations and sign language interpreters, at every step of the way.

Collaboration

Our work with WASLI is supported by the World Federation of the Deaf (WFD), solidified by one of our most important milestones – the signing of the Joint Statement between our organizations. The agreement was signed at the WASLI 2007 conference in Segovia, and every interpreter attending the conference placed his or her signature on the historic statement. I encourage all sign language interpreters to review the document, as it is an explicit statement that guides us in order to reach our common goals. In that agreement, we identified that we would work towards the establishment of sign language interpreter associations in countries where there are none, and establish regional networks of interpreters. The statement stresses the importance of joint working, close liaison and transparent communication between interpreter and Deaf organizations, at the local, national, regional and international levels. Finally, it also states we will share resources with emerging countries.

That important step then led to similar agreements being reached between national association of interpreters and Deaf people, including the National Association of the Deaf and the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf , signing an MOU at the RID conference in Philadelphia. But, while the agreements are a wonderful step forwards, they must translate into positive action among associations.

How Can I support International Development Work?

One: Creating Positive Relationships

The agreements apply to the local level, and so one of the first things we can do is ensure that we are continually contributing to positive relationships among the interpreters with whom we work, and within the Deaf community we serve. These positive relationships start and are sustained by: regular participation at Deaf community events, acting as an ally on issues of importance (example: interpreters attending public rallies in Canada about the closure of VRS services and the impact on Deaf people), volunteering your skills for Deaf community projects (example: translation of ASL letters, committee work, fundraising), and knowing your local Deaf community.

By knowing your local Deaf community, I mean understanding the issues impacting them, their hopes and dreams for their community, and where they stand on interpreting issues. What do they expect of interpreters? Allowing yourself to be known as a person not just a service provider. We cannot model the nature of collaboration between Deaf people and sign language interpreters to others at the regional or international levels if we don’t practice those behaviours in our home communities.

The theme of the 2011 WASLI conference in Durban was Think Globally, Act Locally, exemplified this notion. Our keynote speaker, Colin Allen, now the President of WFD, asked delegates to pay attention to both global developments and local contexts to result in action that betters our communities. An example he cited was the international policy milestone of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). This global policy provides the best guide for people seeking to improve the quality of sign language interpreting services and satisfy the needs of the Deaf communities in local contexts. By extension then, each of us could take the step to become familiar with this document, as it is a document that impacts Deaf people as they advocate for their human rights and services.

Many countries around the world are now using the UNCRPD to work with governments and institutions in order to recognize national sign languages and to support linguistic research about these minority languages, and the Deaf communities that use them. When interpreters are familiar with the language and the power of the UN Convention they are in a better place to support others who are advocating for positive change in emerging countries.

Two: Become Familiar

The second action sign language interpreters can take is to become familiar with the work of the WASLI Educational Task Force. One of the most common requests WASLI receives from countries that do not have interpreter programs is for curricula and resources. Our joint statement with WFD indicates we will share resources with emerging countries. This begs the questions of what and how, which led to the Educational Task Force that worked for the past three years to create guidelines. The guidelines stress the need to recognize the crucial role of local Deaf communities in preserving their sign language(s), and for all program development to occur with the Deaf community. By reviewing these guidelines, interpreters interested in international development can think carefully about the training they will offer in other countries, in order to involve local Deaf communities and interpreters, ultimately with the goal of building capacity within the local context.

The document begins with a philosophical statement:

“…Interpreter educators from countries with established interpreter education will collaborate with educators from countries where interpreter training is not available or is newly developing. Educators will work together to design effective practices and deliver quality education. They will do so in a manner that incorporates local expertise in the cultural, linguistic, social and political conditions that affect teaching and practising signed language interpreting in that country. The goal of collaboration is to ensure accessibility, relevance and effectiveness of training in diverse contexts while maintaining the integrity of national signed languages, customs and norms.”

The aim of these collaborative efforts with local Deaf and hearing community members, Deaf and hearing interpreters, and national Deaf and Deaf-Blind representatives is the development of expertise and empowerment of local personnel to lead the establishment of interpreter education in their respective countries and to support existing and developing national associations of signed language interpreters.

Three: Model International Collaboration

There are several models where sign language interpreters from abroad have collaborated effectively with other regions in order to offer training that is consistent with these “do with, not do for” guidelines created by the WASLI Educational Task Force, and the document highlights examples from Kosovo, Mexico, Colombia and Kenya. By learning about these ways of interacting in other countries, we can lessen the “footprint” of North American ways, ensuring that ASL does not become the default language of use. Philemon Akach, an interpreter and linguist from Kenya, speaks to language colonization in his paper published in the first WASLI conference proceedings, and all of us can learn a great deal from his perspectives on this crucial issue.

If you don’t own the conference proceedings, they are available through the WASLI website.

How Can I Change the World?

Individual Membership

North America is fortunate to have interpreter programs, researchers contributing to the knowledge about interpreting, and organizations that support the development of the profession. By purchasing an individual membership in WASLI you support the many projects in our strategic plan, for example, the task group that are developing communicating protocols for countries that are dealing with natural disasters. Chilean Deaf associations and sign language interpreters had to take governments to court in order to gain access to sign language interpreters on television during an earthquake, while other countries have been able to work effectively with media during these times. By collecting effective practices from the global community, they will produce guidelines that can be used proactively so that Deaf people have access to information, the most basic of human rights.

Donate

Did you know that you could also donate membership fees for sign language interpreters in another country? I choose to support a group of interpreters from Ukraine and it costs me less than five cups of tea. The result is that we are now building a network of interpreters in former Soviet countries and providing them access to materials and documents. Our membership fees are based on GDP formulas, similar to WFD, so while your membership will be less than $50 a year, you can cover the fees for an interpreter from an emerging country for as little as $6.00. What if RID donated $1.00 of every member’s dues to WASLI or your local affiliate chapter did the same?

Sponsor Delegates

Or you as a group of sign language interpreters could choose to start raising funds to sponsor a delegate to our next conference in 2015. Sponsoring delegates from emerging countries is an amazing gift that has a ripple effect. Over the years we have seen interpreters return to their communities with energy, ideas, networks of colleagues, and tools to further develop interpreting in their country, resulting in over 40 new interpreter associations in just 6 years. One of our 2011 sponsored delegates in South Africa spoke of it being a week of “firsts” for him – the first time to see the ocean, to be on an airplane, to see a Deaf interpreter working, to attend a conference about interpreting, and his first time to know that sign language interpreting was a profession.

You can contribute to that kind of life-changing experience.

Attend Conference

In short, there are so many things that North American interpreters can, and I would argue, should do to support the development of sign language interpreting at the global level. One of the most powerful ways that you can learn from others is to attend a WASLI conference and listen to the heart felt stories of interpreters as they present their country report. We have heard about sign language interpreters who walk 2 hours to do an interpreting assignment, and never expect to be remunerated, to the challenges of working as an interpreter amidst the Israeli/Palestine conflict, to the training partnerships between interpreter associations from Colombia and an Ontario chapter of the Canadian national organization, AVLIC.

Volunteer

Finally, WASLI has a devoted group of translators, thanks to Rafael Trevino. He has been a tireless volunteer, bringing together people who donate their time to provide translation in Arabic, Spanish, French, Russian, and so on. Recently, Christopher Stone and Robert Adam, from the UK, accepted the role of translation coordinators for International Sign (IS). Our goal is to be able to get many of our documents into IS which will again increase the knowledge sharing with others for whom English is not their first language. If you are able to offer translation support, be it in a written language or in IS, that is a huge contribution to international development.

Be Part of the Movement

Having a global focus in our changing world is an opportunity awaiting all of us, and I hope that you will embrace the ways in which you can be part of the movement to shape sign language interpreting internationally, and be shaped by experiences of others around the world.

Will you be part of the movement?

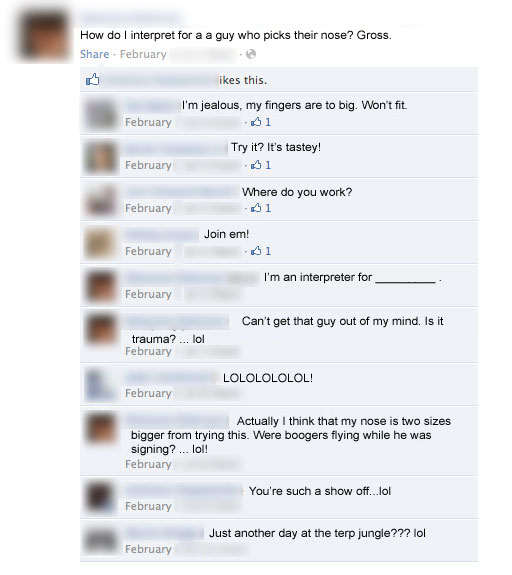

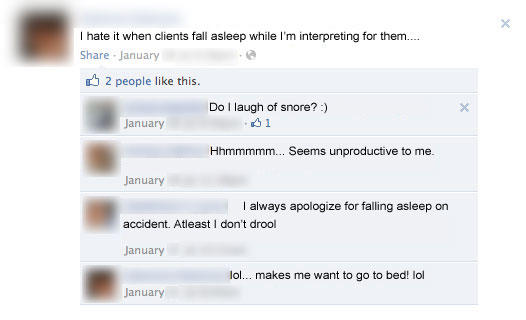

Symptom 4: The Interpreter views digital content as temporary. They fail to understand that digital content, particularly images, will remain forever.

Symptom 4: The Interpreter views digital content as temporary. They fail to understand that digital content, particularly images, will remain forever. When interpreters telegraph opposing political opinions, an emotional disposition, or intimate windows into their personal life, it may lead to reasons for incompatibility with the consumer, and thus the assignment. You may have noticed in the comment section of Brandon Arthur’s post,

When interpreters telegraph opposing political opinions, an emotional disposition, or intimate windows into their personal life, it may lead to reasons for incompatibility with the consumer, and thus the assignment. You may have noticed in the comment section of Brandon Arthur’s post,